The threat of “color revolutions” is a recurring theme in the Russian government security discourse and pro-Kremlin media.

The term was first used to refer to a series of nonviolent protest movements starting in the 2000s that resulted in the overthrow of pro-Russian autocratic and oligarchic governments in Georgia, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia.

The Russian government alleged that these revolutions were instigated by the U.S. and other foreign powers. These revolutions created anxiety within the Kremlin establishment for both domestic and foreign policy reasons. First, the post-revolutionary governments adopted a more pro-Western orientation and thus, seen as less malleable to Moscow’s influence. Second, and perhaps even more importantly, they fuelled fears of a color revolution demanding democratic rights inside Russia itself.

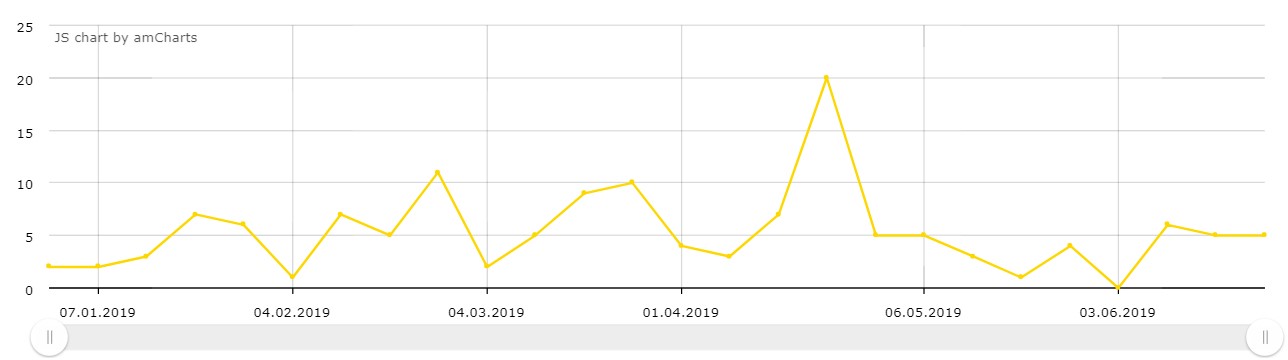

It is little wonder then why the pro-Kremlin media is so fixated on color revolutions. The International Republican Institute’s (IRI) Beacon Project used its proprietary media monitoring tool >versus< to track approximately 145 of the most visited online Russian-language media from January to July 2019 and found 138 articles referencing the color revolutions. References spiked in April, driven by reporting from the Russian pro-Kremlin website Lenta.ru alleging that Russian security services had uncovered an American plot to instigate color revolutions in Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela.

Online publications referencing of color revolution in Russian

The idea of an external threat has always played an important role in the strategic communication of Soviet and Russian leadership. Today, the Russian government uses fears of an external threat as a justification to crack down on any public expression of anti-establishment sentiment. For example, Russian authorities regularly label organizations that empower civil society and media, and/or receive foreign funding as foreign agents.

Valery Gerasimov, head of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces, argued at an April 24 public event on international security that Western intelligence agencies hypocritically employ “hybrid” warfare against Russia, all the while falsely blaming Russia for using the very same tactics against the West. Thus, we can see that the internal thinking of the Russian elite is that by empowering civil society, information and technological warfare, the U.S. is forming a negative image of unfriendly governments domestically and in the world, and consequently using it to topple them.

In March 2019, the Federal News Agency, which reportedly emerged from the infamous Russian “troll factory” in St. Petersburg, published what purported to be an investigative piece about an attempted U.S.-backed color revolution in Madagascar. The following month, Sergey Veselovsky, of the Russian International Affairs Council, a Russian-government think tank, floated the possibility of “a color revolution, which is being prepared by the Americans” in Serbia. He further claimed that if Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic, a Kremlin ally, refuses to heed the wishes of the U.S. State Department by joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and downgrading Serbia’s close ties with Russia, Vucic may be forced out of power and even be “physically liquidated.” Veselovsky was reacting to the protest marches criticizing the country’s democratic backsliding and corruption under Vucic and demanding his resignation that have been taking place every weekend in the Serbian capital of Belgrade since December 2018.

In July, the Deputy Secretary of the Russian Security Council Rashid Nurgaliyev, claimed that NATO is cooking up color revolutions and that it “[…] is laying the groundwork to put the west-controlled regimes in power in a number of CSTO countries.” The CSTO, or the Collective Security Treaty Organization, whose members are Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, is a pet project of Kremlin. Many Russian analysts see the CSTO as an attempt to replicate NATO, even if Russia insists that it’s fundamentally different. However, CSTO’s effectiveness is questionable. Writing in 2015, Pavel Baev, a Russian-Norwegian analyst at the Peace Research Institute Oslo, pointed out that Russia had “little success” in terms of “building reliable structures that could legitimize and substantiate its role as a major security provider in the post-Soviet space.” In recent years, CSTO has had trouble holding meetings. Currently, CSTO members can’t even agree on the approval of a new secretary-general.

Whether stemming from genuine conviction or a strategy of deliberate disinformation on the part of the Kremlin establishment, the color revolutions are portrayed as part of the hybrid war arsenal the West aims at Russia and its allies. The Russian media is willing to spread conspiracy theories that label protest movements against authoritarian and oligarchic governments — whether close to home or far away — as engineered by the West. This propaganda serves as a smokescreen for Kremlin’s own actions of instigating political unrest and division in other countries. In Ukraine, Russia’s malignant information campaigns provided a pretext for a full-scale Russian occupation of Crimea and aggression in eastern Ukraine. During the yellow vest protests in France, the Kremlin was suspected of having spread disinformation to portray France as a country in turmoil and encourage further protests. And throughout Europe, the Kremlin has developed close and worrisome ties with European far-right parties and organizations to fuel Eurosceptic views.

Kremlin has much to gain by spreading disinformation and political unrest among its neighbors. Kremlin’s willingness to do so is why it is so important to continue to monitor Russian disinformation using IRI’s >versus< tool and other latest technological advances to defend democracies and democratic movements worldwide.

Top