Sino-Angolan Cooperation: Mutually Beneficial or Neo-Colonial?

Angola is Africa’s top oil producer and one of the fastest growing petro-economies in the world. Despite robust economic growth, it’s GINI Coefficient of 58.6 – a standard indicator of inequality within a society – suggests that gross economic disparities remain. Since the end of a twenty-seven-year civil war in 2002, most Angolans have been forced to endure a very low standard of living.

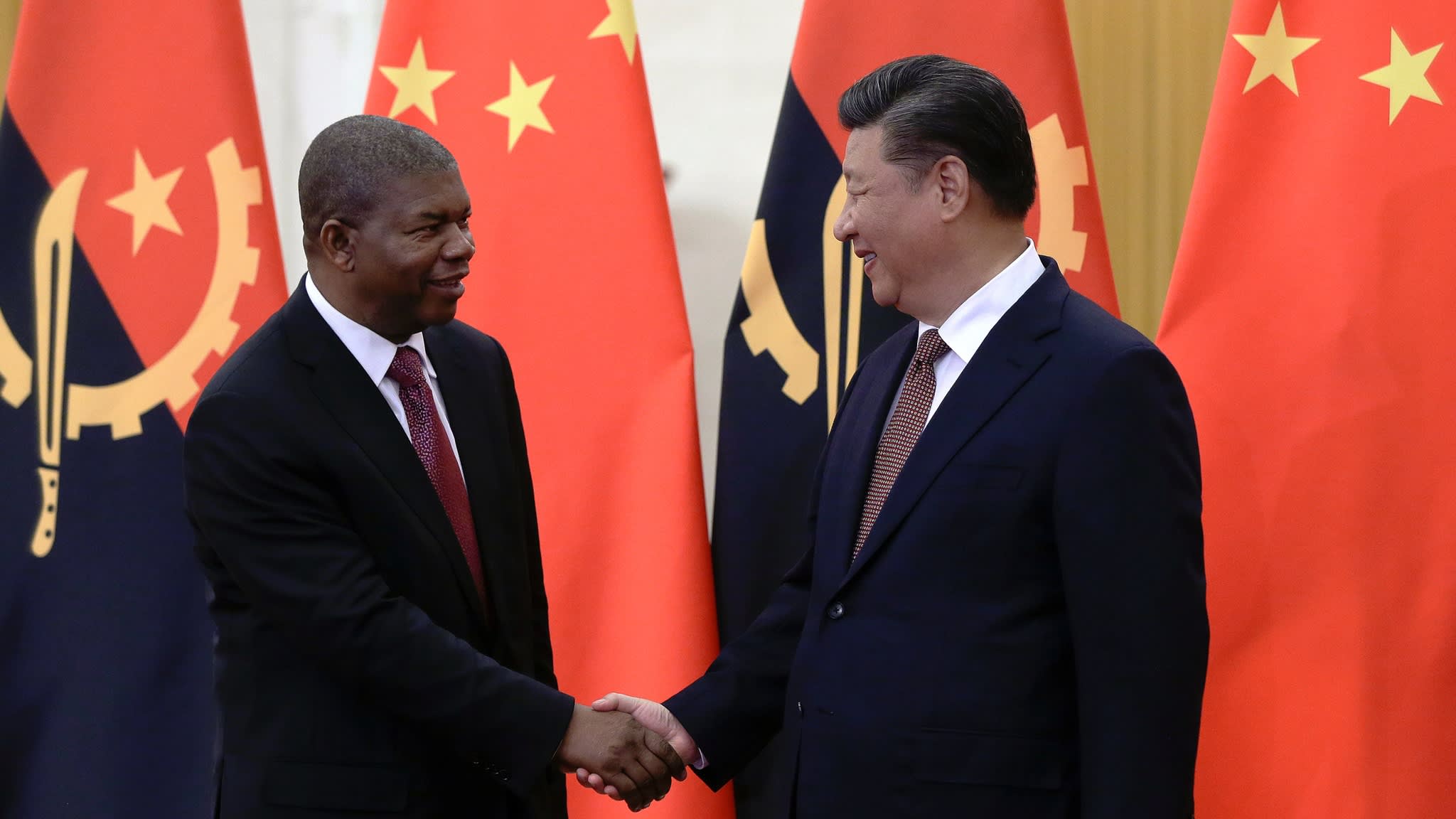

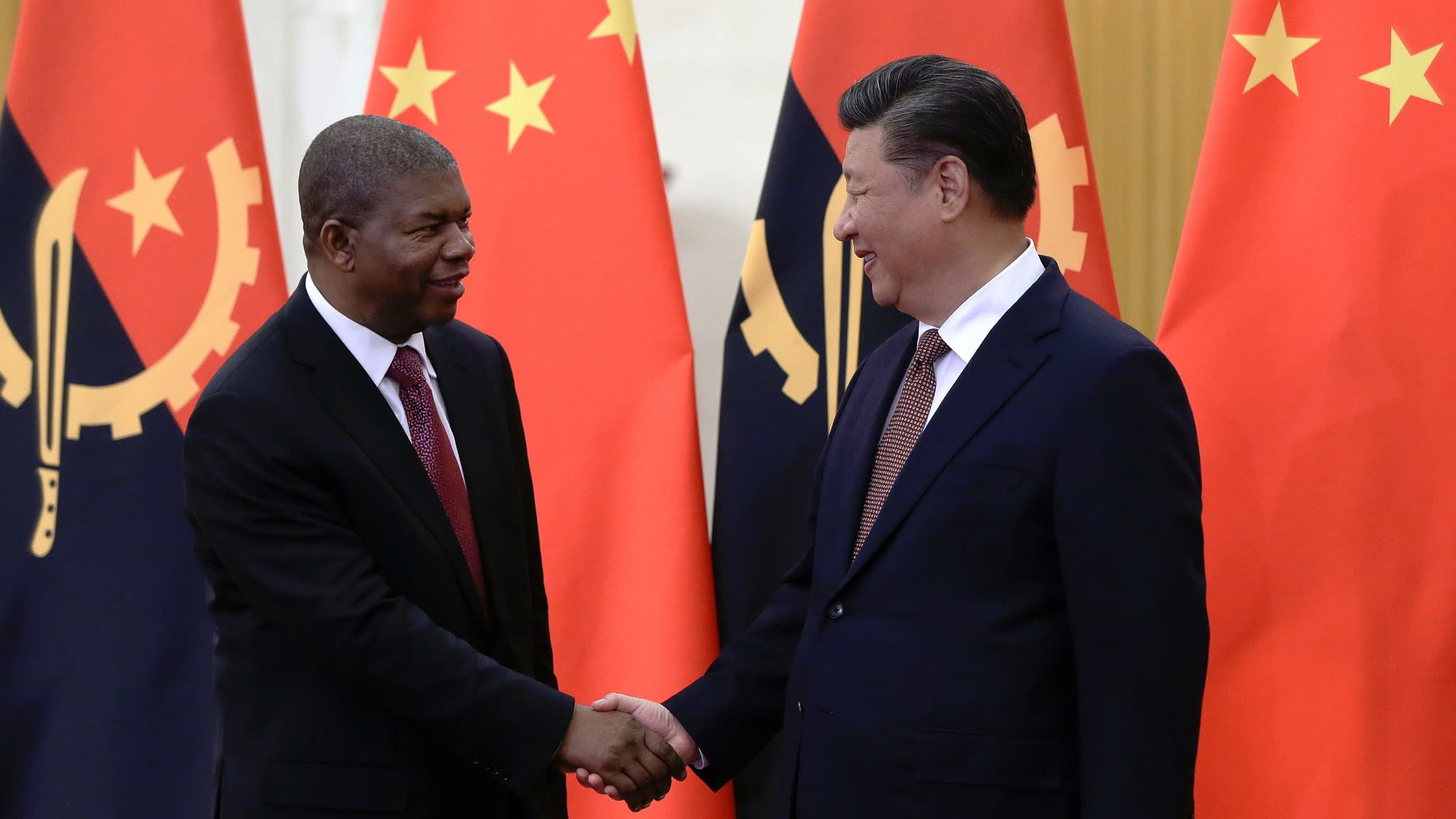

In August 2017, Joao Lourenco won the Angolan presidential election after incumbent President Jose Eduardo dos Santos stepped down. Since his election, President Lourenco, or J-Lo for short, has made considerable promises to diversify the Angolan economy but in practice has continued to rely on natural resource exportation as his fallback position. Recently, Angola has shown interest in diversifying its economy and has been successful in this goal by increasing production in the construction and manufacturing sectors. Although a few sectors have seen relative and incremental growth, Angola’s annual GDP is still up to largely reliant on oil exportation with only small contributions from agriculture, telecommunications and fishing.

Angola’s attempt to broaden its economy by engaging with China is highlighted by several oil-for-infrastructure trade deals. This approach is known commonly as Angola Mode. Angola Mode is framed by China as a “win-win”— Angola trades its vast natural gas and oil commodities for much needed infrastructure projects including railways and medical facilities. In 2006, during a visit from the Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, President Dos Santos said, “China needs natural resources, and Angola wants development.”

As a result, Angola’s annual GDP is over 60 percent reliant on oil and natural gas exportation which prompts several concerns regarding their economy. When Angola cannot afford their debt repayments in cash, the Chinese lending institution is functionally granted control over the oil blocks that failed to generate the cash to make the full oil payment – thus effectively giving China autonomy of the oil and natural gas production sector until the monetary value of the payment is fulfilled.

Although this deal is the underlying structure of the “win-win” relationship promised by China, it could very quickly and easily turn disastrous for Angola if they fall too far behind on their payments. Thus, Angola’s oil can be directly utilized as collateral to finance its credit similarly to how Ethiopia was able to pay back its Exim Bank loans in sesame seed exports in 2009. For Angola, natural resource-based collateral will have more lasting effects: because the economy is so entrenched in oil exportation, it would be difficult to prioritize repayments without falling further behind and creating a cycle of eternal debt.

Another obstacle to Angola’s economic development is the state-run oil company, called Sonangol, which has been a focal point for oil-based corruption. Since its creation in 1976, it has controlled over 50 percent of oil production in the major oil-producing provinces as well as many offshore concessions. Sonangol also oversees licensing for exploration and production which determines the oil profit due to the government, as well as its payment to the finance ministry. Sonangol has been cited as one of the main obstacles between institutional legitimacy, transparency and good governance because it is the high-profile link between Angola’s political elites and oil exportation revenues.

While China emphasizes the mutually beneficial nature of this relationship, many experts argue that China’s role is predatory and neo-colonial. One major concern is the influx of Chinese migrant workers to the African continent. The Chinese promise of infrastructure under the oil-for-development deals is often built by Chinese migrant workers, not Angolan companies. Thirty percent of construction contracts are supposed to be awarded to Angolans, but the arrival of migrant workers has created intense competition that many local companies cannot compete with. Such a dynamic results in a skills gap and a glut of unfilled positions, because the CMWs typically live in Chinese-only compounds with little-to-no exposure or integration with the indigenous Angolan population. After completing their specified projects, more frequently than not CMW move home to China before they can pass down their technical knowledge and skills to the indigenous workforce.

One final condition of China’s investment in Angola is that many local Angolan companies struggle to remain competitive in cheaper markets flushed with imported Chinese products. China’s focus on manufacturing clothes and shoes has filled Angolan markets with cheap products and pushed local companies who do not receive partnership agreements with Chinese firms out of the market.

The deal outlined in Angola Mode is not new to Africa, but illustrates one of several strategic approaches that China has implemented on the continent. Chinese investors have demonstrated their commitment to resource extraction to power China’s vast domestic manufacturing sector– a growing trend typical of authoritarian influencers on the African continent. This is one of the main reasons why organizations who promote democracy and good governance, like IRI, are especially important now. Countering the spread of Chinese authoritarian influences in countries like Angola must be a top priority in the United States’ current and future African policy.

Top