Antisemitic Discourse in the Western Balkans: A Collection of Case Studies

Executive Summary

The purpose of this publication is to provide a complex analysis of antisemitism in the Western Balkans. In cooperation with a team of researchers, the International Republican Institute (IRI) conducted online media monitoring to determine the most common narratives related to antisemitism and the relationship between Western Balkan societies and the local and international Jewish community. The publication contains seven country case studies analyzing online media narratives in the light of each country’s specific historical, legal, and societal background. The aim is to provide information that can be used to assess resilience against antisemitism and hate speech and recommend solutions for identified policy gaps.

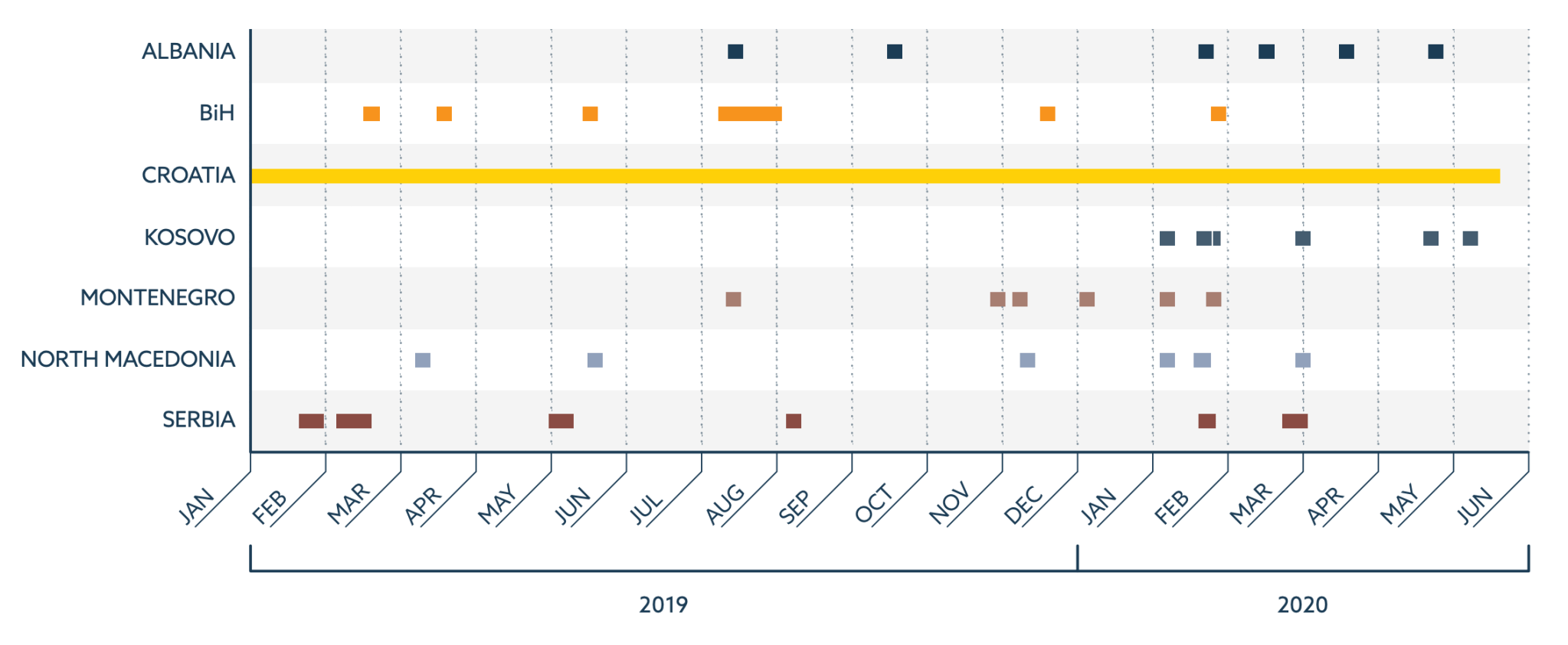

The seven countries covered in case studies are Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Albania, and Montenegro. Locally based IRI partners were tasked with monitoring online media spaces in these countries and analyzing the content of selected online news sources, Facebook sources, and related readers’ comments sections published between January 2019 and May 2020. Furthermore, these partners hand-coded online media content, which allowed them to assess how widely spread particular types of antisemitism are.

Researchers examined more than 9,000 online media pieces. Although instances of antisemitic speech in online media did not exceed 4 percent of examined content, the research indicated several threats that might affect the increase of antisemitism, as well as susceptibility to other forms of extremism. The urge to assign responsibility for specific historical events and the establishment of common regional historical memory is the overarching context into which narratives related to Jews in the Western Balkans are fed. Antisemitic narratives were not substantially different from narratives seen in other parts of Europe and mainly contained familiar conspiracy theories about control of world financial markets, as well as modern conspiracies such as those claiming intentional development of COVID-19. Besides conspiratorial content, violent and vulgar antisemitic language was common. What seems to be specific to the Western Balkan region is the use of antisemitism (and often the use of a certain form of philosemitism) as a tool to sow or intensify regional conflicts. Holocaust remembrance was often used as a pretext for criticism of crimes of one ethnic group against another, and Holocaust crimes were used in many online media pieces as a comparison for crimes committed during the 1990s.

Narratives about wars of Yugoslav succession often link those conflicts with the events of World War II. As there is no common regional historical memory of the succession wars, the interpretation of events around World War II is also affected. Purposeful misinterpretation or utilization of historical events in populist narratives represents a threat to peaceful democratic transition in the region. This issue is even more serious in relation to insufficient attention to Jewish legacy and antisemitism in areas such as education or the preservation of historical sites.

Although the research didn’t find an abundance of antisemitic statements in examined sources, it did confirm the use of antisemitism in local politics and the utilization of international antisemitic narratives as a tool for amplifying other political narratives. Limitations in legal and law enforcement frameworks and the accessibility of extremist literature could contribute to the rapid increase of antisemitism. Public engagement of local Jewish communities is essential for achieving policies protecting the rights of minorities and cultivating public debate.

Introduction

Seventy-five years since the Shoah, in which 6 million European Jews perished, antisemitism is still present in European society. As United Nations (U.N.) Secretary-General Antonio Guterres noted, “antisemitism is not a problem for the Jewish community alone.”1 It is an indicator of wider societal tendencies: “where there is antisemitism, there are likely to be other discriminatory ideologies and forms of bias.”2 According to public opinion research conducted by the European Union’s (E.U.) Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), 89 percent of European Jews surveyed felt that antisemitism has increased in the past five years.3

With its data-driven approach to strengthening the resilience of European democracies, IRI’s Beacon Project seeks to increase the capacity of local actors, such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and state institutions, to understand the prevalence, nature, and scale of antisemitism and other forms of hate speech in the Western Balkan countries — and, more specifically, the region’s online media space — in order to inform policy responses.

IRI’s Beacon Project

IRI established the Beacon Project in late 2015 in order to better understand and improve responses to malign foreign influence. The Beacon Project remains IRI’s primary response to the Kremlin’s campaign of interference which is being waged across Europe. It identifies the dynamics that allow state-orchestrated meddling tactics to thrive, while assisting stakeholders in crafting effective responses.

This publication is IRI’s first effort to apply its effective monitoring methodology to study antisemitic narratives. The focus of the current research is identifying and tracking thematic malign narratives being spread throughout the Western Balkan region, regardless of their geographic origin.

Data-Driven Approach

In 2018, 25 of the 57 Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) participating states reported antisemitic incidents, according to official state sources.4 A further 1,950 incidents, including threats and violent attacks against people and property, were reported by other sources.5 While such numbers are worrying, the true extent remains unknown due to limited monitoring and reporting of antisemitism and other forms of hate speech. The U.N.’s Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights estimates from available data that the number of antisemitic incidents worldwide has increased by 13 percent between 2017 and 2018.6 By the U.N.’s own admission, the available data worldwide remain limited and antisemitic incidents remain significantly underreported, despite data being collected by an increasing number of NGOs concerned with the situation and seeking to fill the voids in official state data. One reason for this is that state monitoring mechanisms remain largely non-existent or, where they do exist, tend to lack specific focus on and consistent monitoring of antisemitism. Moreover, while 89 percent of European Jews surveyed in 2018 by the FRA felt that antisemitism increased in their country in the five years before the survey and assessed it as most problematic on the internet and on social media, monitoring of antisemitism online remains limited.7

To close this gap in the Western Balkans, IRI cooperated with local researchers in each country who monitored online media in local languages to identify instances of antisemitism and hate speech. This media monitoring was combined with interviews and desk research in which researchers gathered information about existing legal and policy frameworks and provisions, formal mechanisms for reporting antisemitism, and civic initiatives engaged in addressing antisemitism and the historical backgrounds of antisemitism.

Using the data collected by applying the >versus< media-monitoring tool, ten researchers from Serbia, Bosnia, and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Croatia, Kosovo, Albania, and North Macedonia produced analytical reports about the frequency and character of antisemitic narratives in the online media space, including details about media platforms that propagate these narratives.8 Their media-monitoring analysis was incorporated into case studies for each country.

Methodology

This study combined three main research methods: desk research (using sources such as human-rights indexes, other reports of international organizations, and governmental reports), interviews with relevant stakeholders (e.g., representatives of Jewish communities, academics, and NGO representatives), and monitoring of selected online media using the >versus< online-media-monitoring tool, which is further described below.9

IRI’s research, conducted in cooperation with local researchers, aimed to go beyond the collection and classification of antisemitic language/statements present in Western Balkan online media (including social media). The emphasis was on better understanding how antisemitic statements correlate with events reported in media and what topics and narratives are created by these statements. To answer these questions, it was necessary to focus on a wide selection of media to get a representative sample of the whole media space and monitor not only instances of antisemitic statements, but the overall approach of Western Balkan media to the topic of antisemitism and Jews in general.

As Jewish communities in this region are small and not very publicly active, it was assumed (and proved in the initial testing) that online media would likely mention Jews and related topics only under specific circumstances (such as historical anniversaries, instances of antisemitism abroad or international politics). The research team wanted to see which of these circumstances spark media interest and whether they trigger antisemitic reactions. Knowing if an occurrence of antisemitic statements has any relation to online content trending shortly before or after the occurrence helps to determine whether those statements are an isolated incident or feed into a larger narrative. Knowing under which circumstances media report about Jews and related topics helps to further determine what these narratives are, whether they have a national or international focus, which vulnerabilities they potentially try to exacerbate, and why they do so. Identification of narratives in the media was also made possible thanks to data research of each country’s local historical, social and political background.

The research was also intended to assess the risks of antisemitism and provide recommendations to combat it. Insight into general reporting about Jews, together with research regarding the current place of Jews in Western Balkan societies, helped to better estimate gaps in education and access to information among stakeholders such as other researchers and policymakers. Research regarding legal and institutional mechanisms against antisemitism further helped to provide answers about the state of resilience in the relevant countries.

Media-Monitoring Sources

The online media analysis served as the primary means of gathering quantitative data for each country case study.

Researchers examined both public and private online media and worked with a total of 341 unique media outlets across the region, including a mix of national and local outlets. In addition to high-readership, or mainstream media, researchers also monitored “fringe” media sources and sources widely known for spreading hate speech targeting the Jewish population.

Researchers worked with three types of online media sources:

- News — The vast majority of websites in this category are online versions of mainstream and fringe media outlets, but this analysis also included associated blogs or popular personal websites creating online media pieces such as news content, blogs, or other articles. “News” is a broad label for different text forms, including articles, editorials, essays, blogs, reportage, etc.

- Discussions — This is defined as reader comments on aforementioned news sources (so-called “under article comments”). The media sources are the same as above, but the focus is purely on commentary written by third parties rather than the main text.

- Facebook posts — Facebook data were collected, however, in a smaller number than anticipated, due to a change to Facebook policies that restricted access to data during the project. Facebook posts represent less than 12 percent of online media sources.10 Sources in this research mostly represent Facebook pages of mainstream and fringe media, though others represent Facebook pages and public profiles known for antisemitic hate speech.

The sources were comprised of online media that are based in, or have a significant readership in, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Kosovo, and Albania. Access to historical data of Albanian-language sources in Albania and Kosovo was limited, as many online media in these countries do not archive data longer than several months.

Time Scope

Online media monitoring was conducted between January 1, 2019, and May 20, 2020, and used the time peaks method. The original one-year monitoring period was extended during the testing phase because of the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe (which, based on preliminary test monitoring, turned out to be fertile ground for antisemitism).

The decision to focus on a long period of time was made based on test monitoring of antisemitism, using the most common explicitly antisemitic language as keywords. However, this monitoring revealed only a handful of results per month (almost all in discussions and Facebook), and even usage of general keywords such as “Jew” didn’t show more than 20 results per month in some countries. Therefore, it was clear that the research should be broadened to a much longer period of time in order to produce a relevant amount of data to analyze. Testing monitoring determined five general keywords that could locate content covering or containing antisemitism.11 Their high generality ensured that online media content pulled by >versus< would contain both antisemitic statements and general reporting (as discussed above, research focused on both for a reason). These five keywords proved sufficient, as testing showed that adding additional and more specific potential keywords would not increase the total number of results in a given period. Monitoring using general keywords over a long period of time was an ideal solution for most of the countries. Serbia was an exception. With Serbia being the biggest media market in the region, the chosen method would require reviewing tens of thousands of online media pieces. Therefore, the research team decided on a compromise that allowed researchers to focus on a long period of time but analyze a reasonable number of online media pieces.

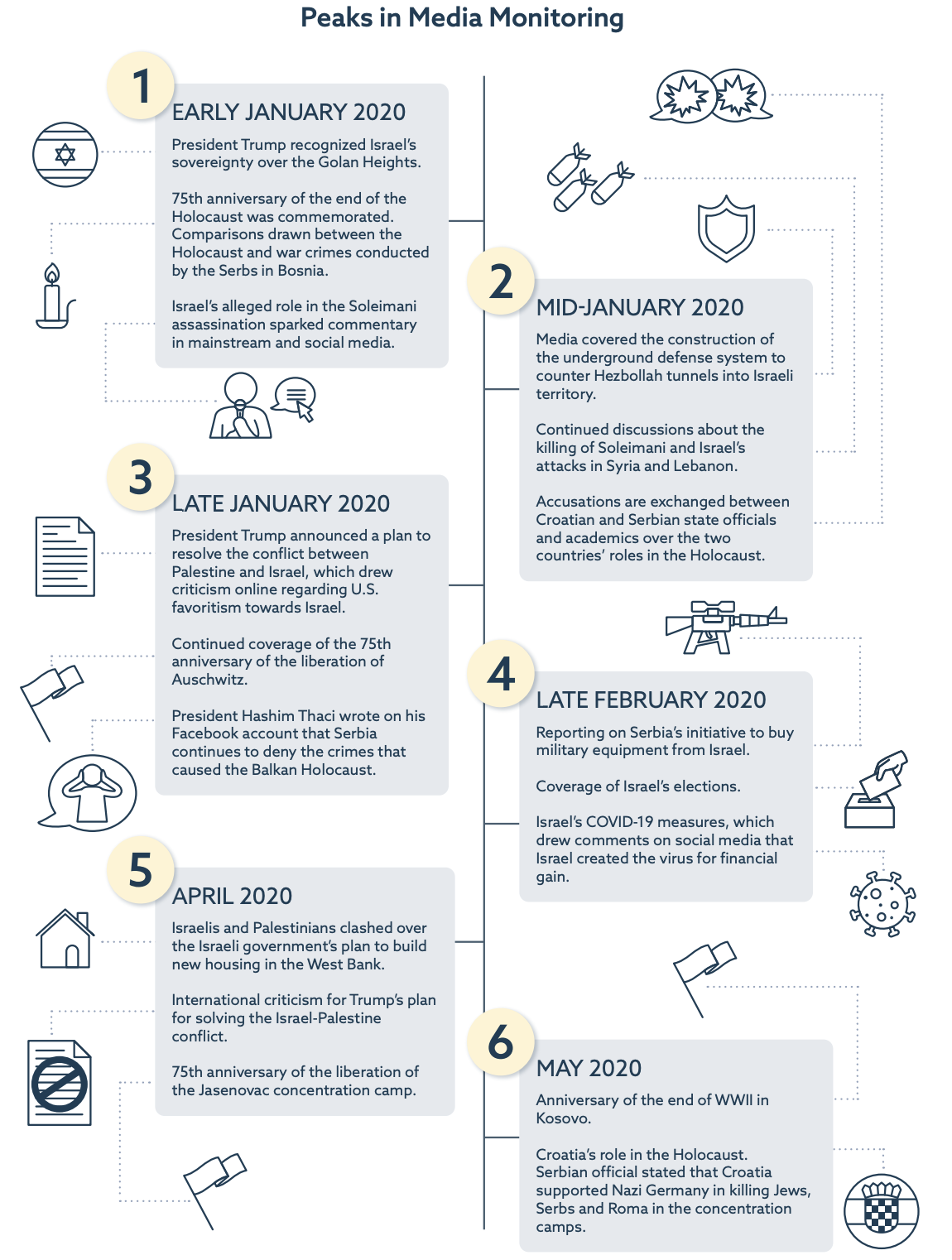

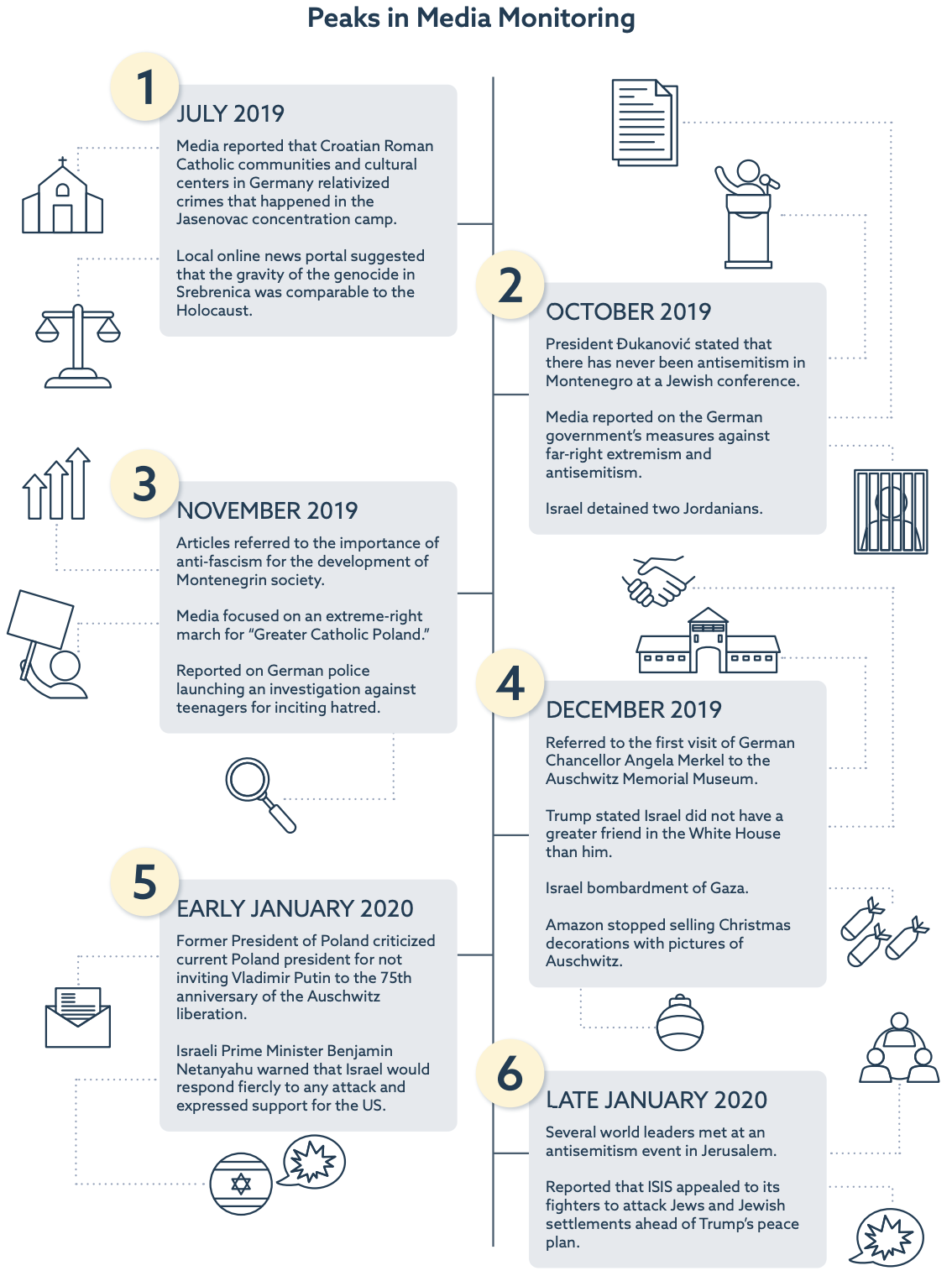

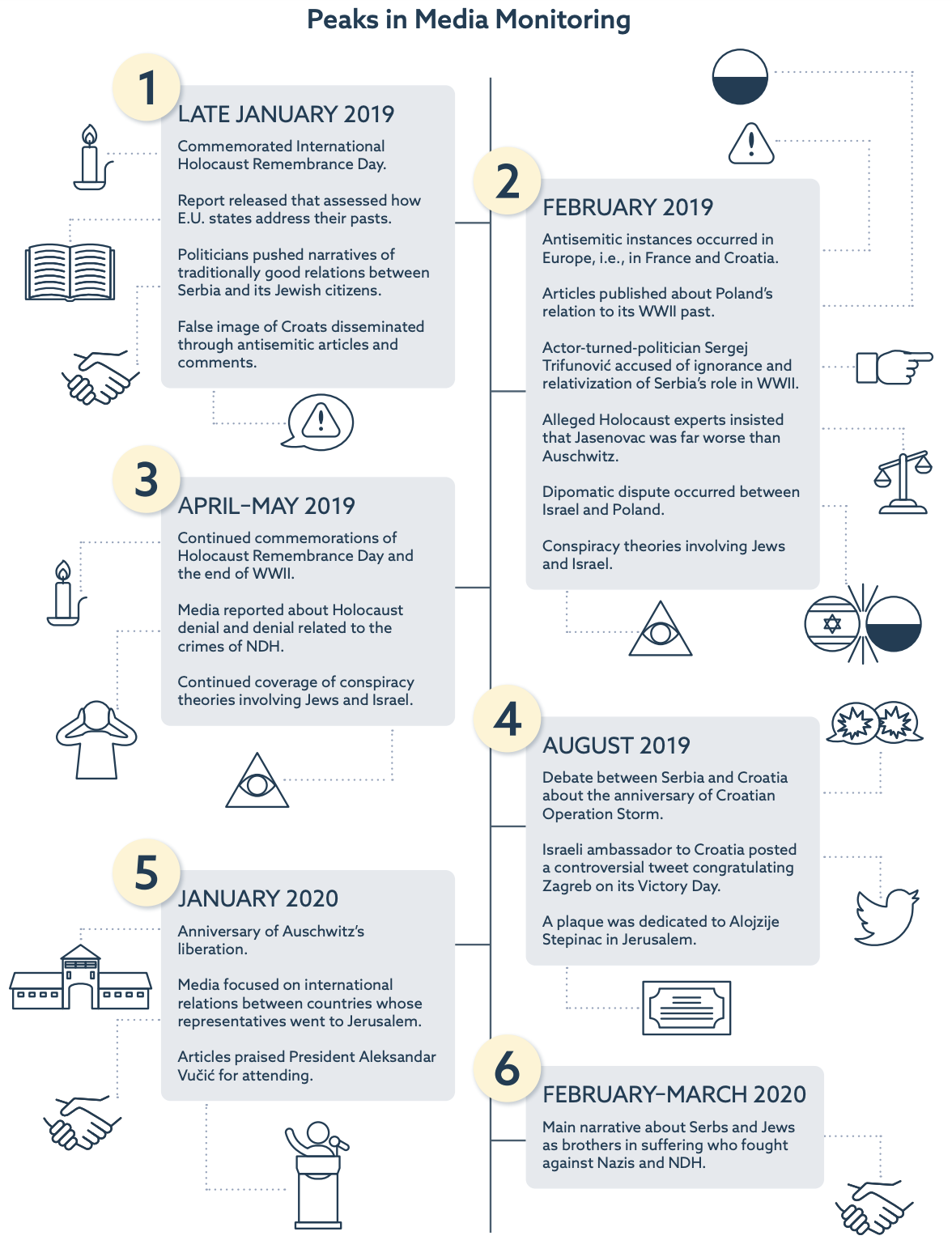

Instead of monitoring online media content produced on each day of the selected period, the research team focused only on periods that showed the highest concentration of content related to antisemitism (or Jews, more broadly), based on a set of selected keywords.

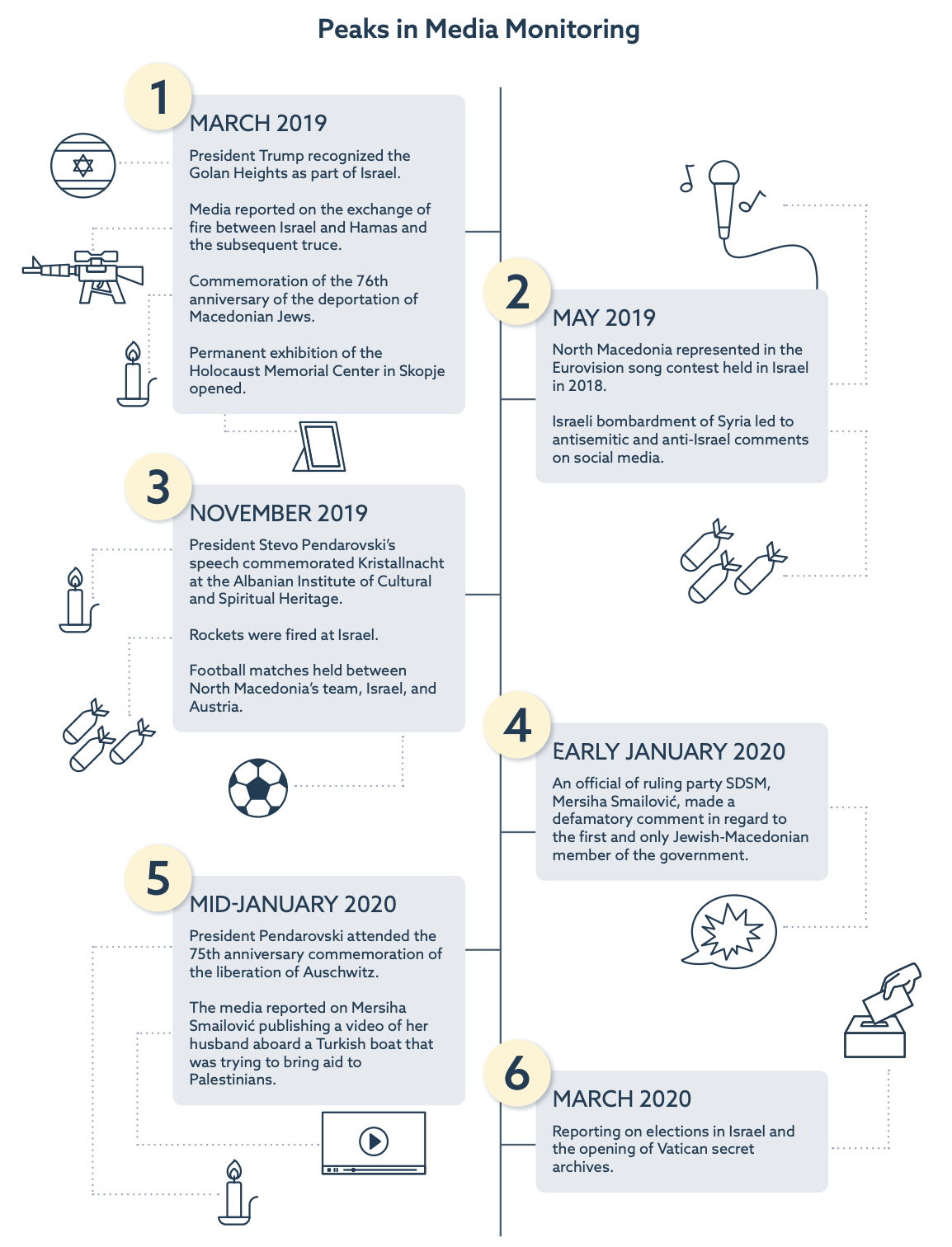

As a next step, the research team selected the six highest peaks in each country, and researchers were asked to monitor three days before and three days after the indicated peak in order to collect data that would help to explain what caused a particular peak and what were the reactions to it.12 As shown in the graph depicting time peaks in each country case study, time peaks in each country were slightly different, although partially overlapping.

Media-Monitoring Components

In order to answer the research questions stated above, country researchers conducted online media monitoring consisting of three components:

- Examining how the issue of antisemitism is covered by media in each country, and the region overall, by identifying and categorizing content from local media describing/discussing instances of antisemitism during selected time peaks. The categorization was developed by Beacon Project staff based on the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism.

- Determining the degree to which online media employ antisemitic language and/or narratives by identifying and categorizing antisemitic statements.

- Researching the dynamics between the Jewish community and the general population to gain an understanding of specific relationships between those communities and their representatives in the country and beyond.

Categorization of Antisemitism

The categorization of antisemitism is guided by the working definition of antisemitism adopted at the IHRA plenary meeting in Bucharest on May 26, 2016. The IHRA brings together 34 countries (including 25 E.U. countries) to preserve the memory of the Holocaust in order to ensure it is never repeated. These member countries are accepted into the IHRA according to the terms of the Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust and, upon acceptance, nominate high-ranking officials and experts to serve on their national delegations to the IHRA.13 Intergovernmental bodies may cooperate with the IHRA as a partner to participate in and gain access to IHRA developments. The E.U. became a permanent international partner of the IHRA in November 2018. Among the Western Balkan countries, two are IHRA member countries (Croatia and Serbia), one is a liaison country (North Macedonia), and two are observer countries (Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina). Only North Macedonia, Serbia, Kosovo, and Albania have officially endorsed the definition, the core part of which follows:

Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.

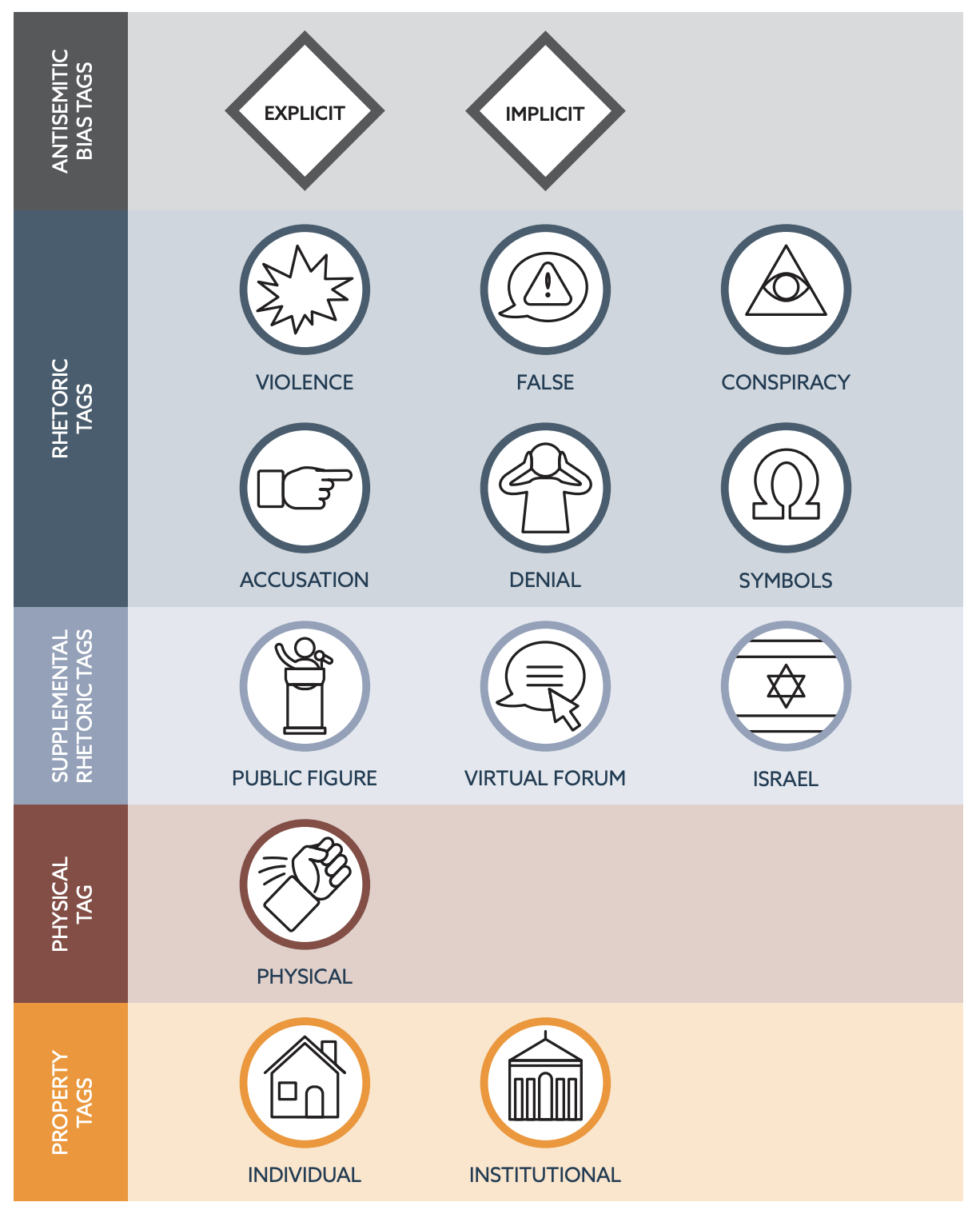

Using this definition, IRI prepared a list of tags to categorize instances of antisemitism based on the presence of certain messages or values, as well as specific actors and countries. Tags, defined by the researchers, were added to the articles to facilitate recording various findings on harvested data. These tags were used to annotate analyzed online media pieces in order to categorize them, according to the table on page 19.

The tags table shows the categorization of the tags IRI staff formulated based on the IHRA working definition of antisemitism.14 The categorization helps determine whether the antisemitic incident is rhetorical15, physical, or related to property. The text below provides detailed definitions and examples for tags that were used to supplement the main categories. Researchers also developed a few additional tags to help them capture specific trends in their country (for instance, a “good relations” tag was used in Albania to calculate occurrences of media mentions stressing good diplomatic relations between Albania and Israel).

Researchers focused on two overarching categories of antisemitic incidents. First are results that report on an instance of antisemitism in the world. The second category of results contains antisemitic statements themselves. In this case, the antisemitic bias tags were used. The following tags were intended to denote whether these incidents of antisemitism were implicit or explicit within the content, as further defined in the table. The research team also developed a set of five tags to categorize themes and biases relevant to instances of antisemitic rhetoric (written or spoken) and three supplemental rhetoric tags: one tag to annotate physical incidents and two tags to annotate incidents related to property.

In addition, researchers used a “flag” tag to annotate online media pieces that contained hate speech that violated common community standards (researchers used Facebook hate-speech policies for guidance) and should be reported to the platforms hosting this content.16 Finally, researchers used context tags, such as the relation of content to a relevant country (in the form of the ISO alpha-2 country code for each nation), or public figures (such as Vladimir Putin or George Soros), in order to gather more information for their analysis.

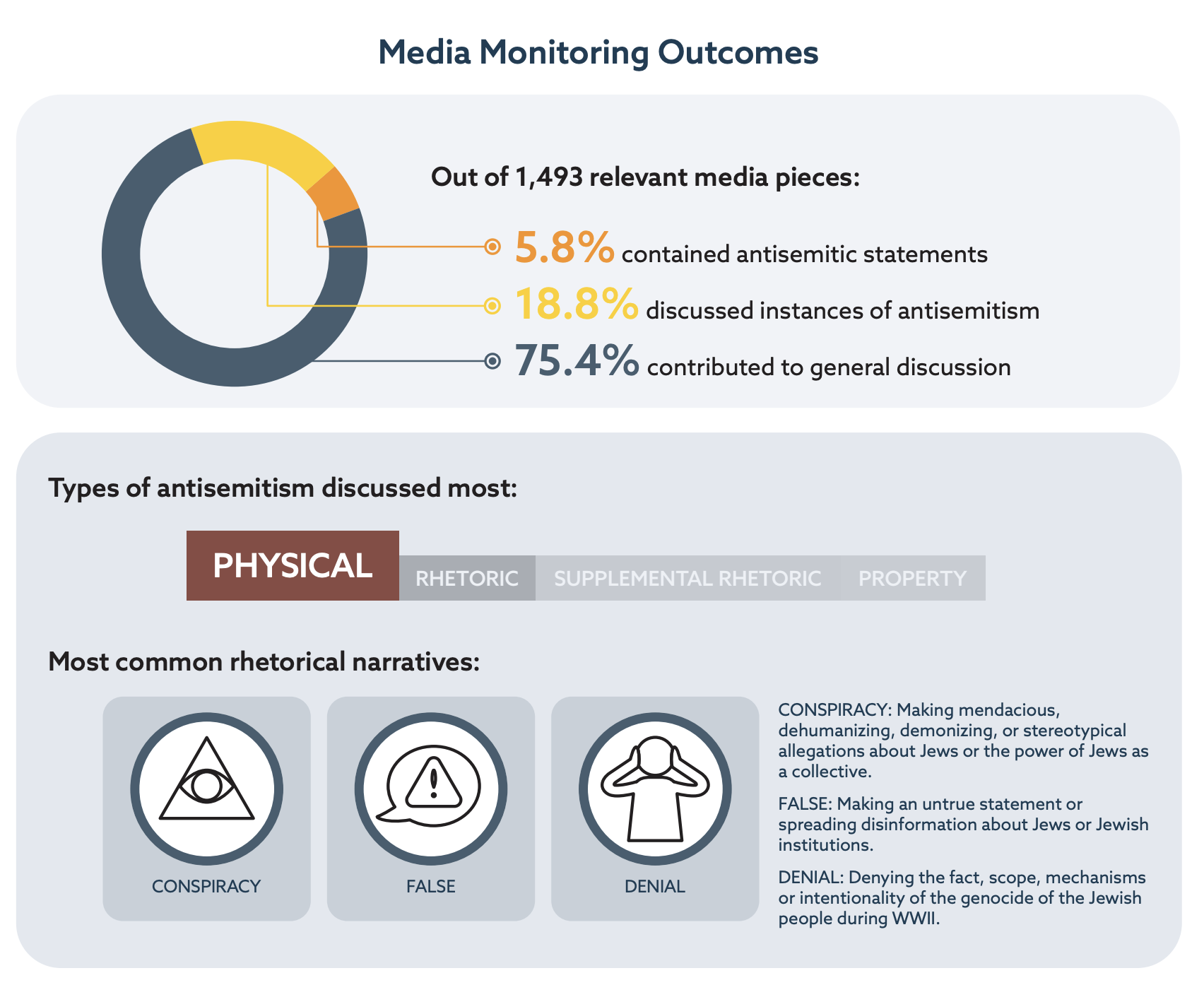

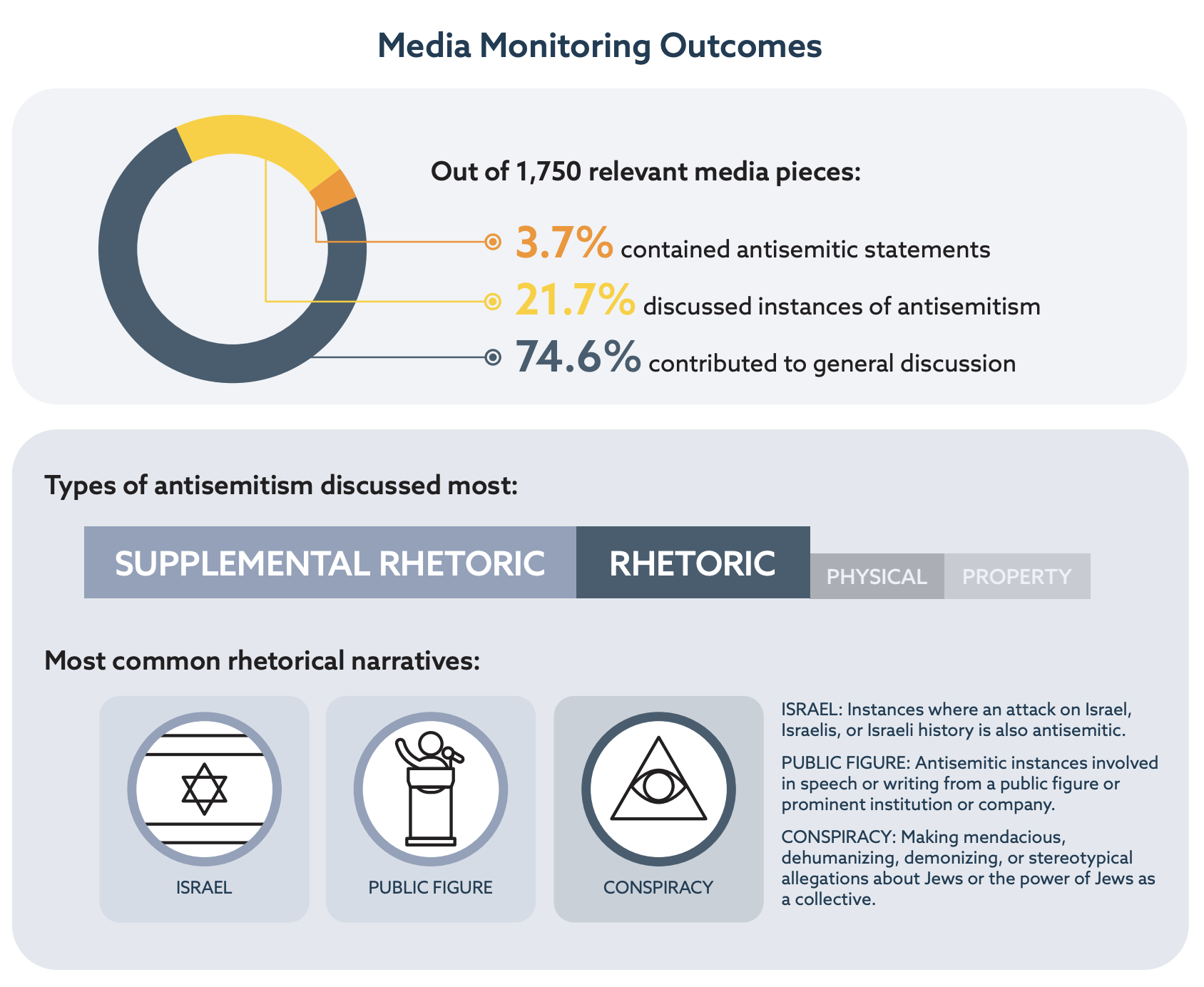

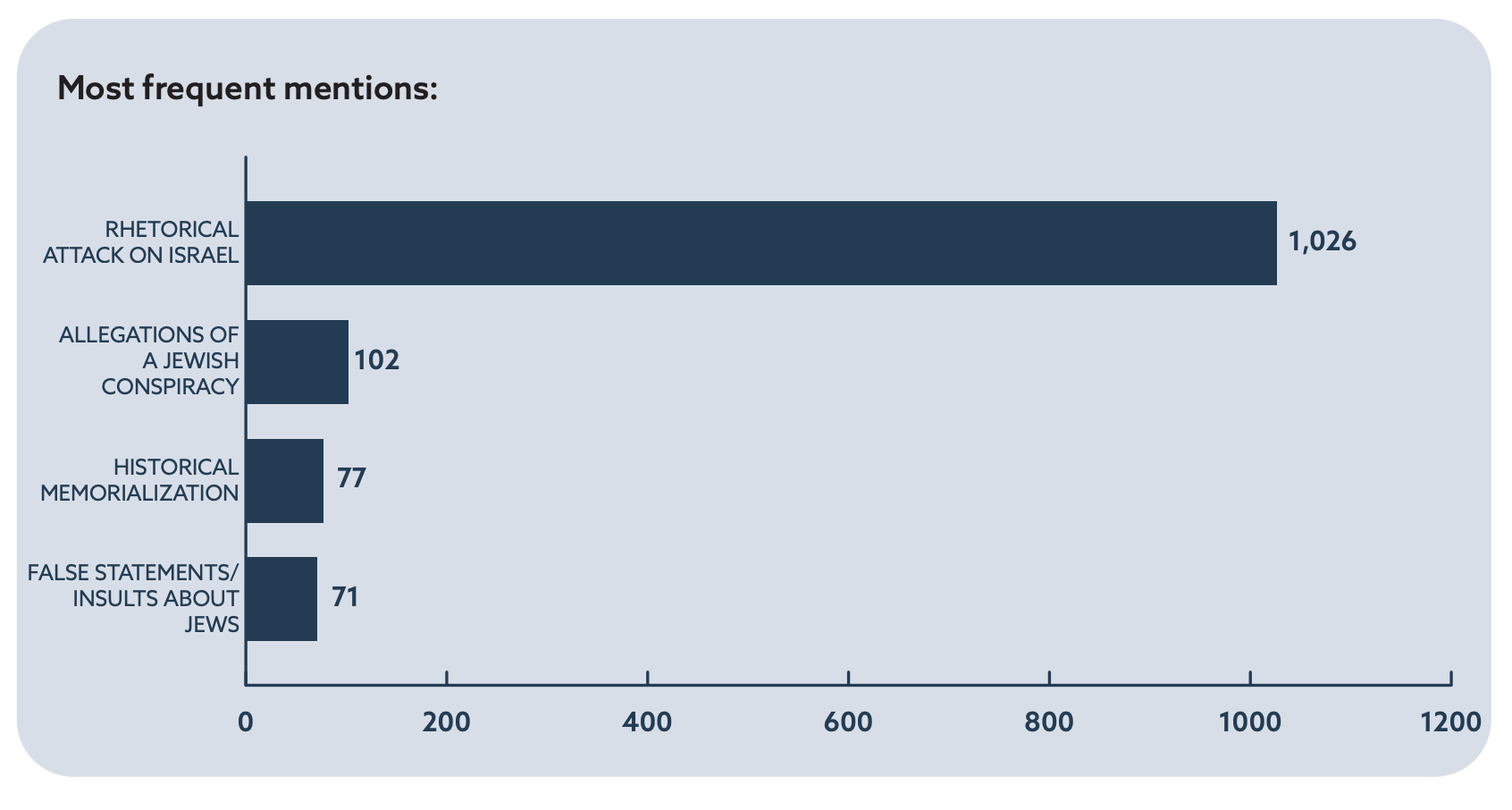

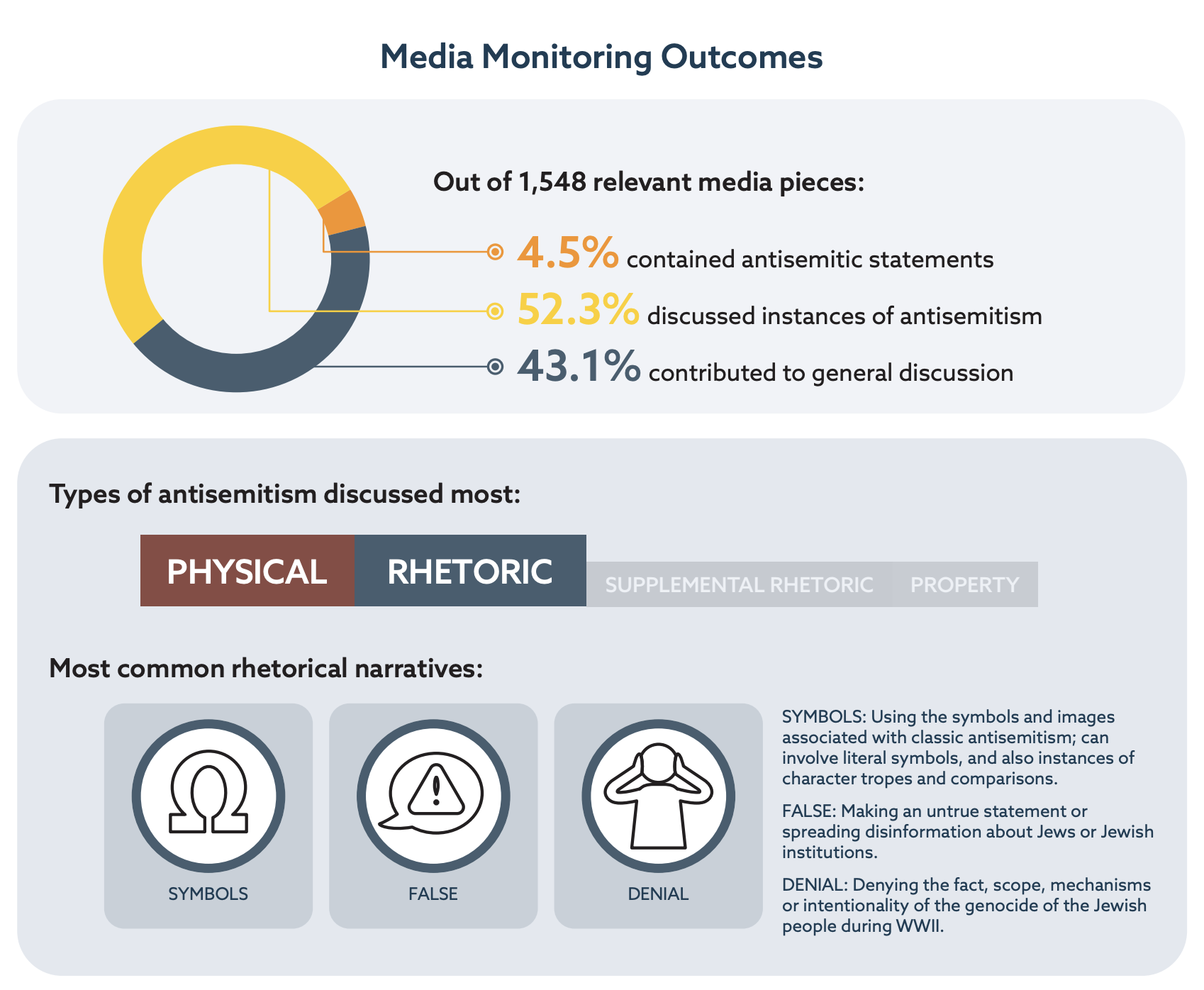

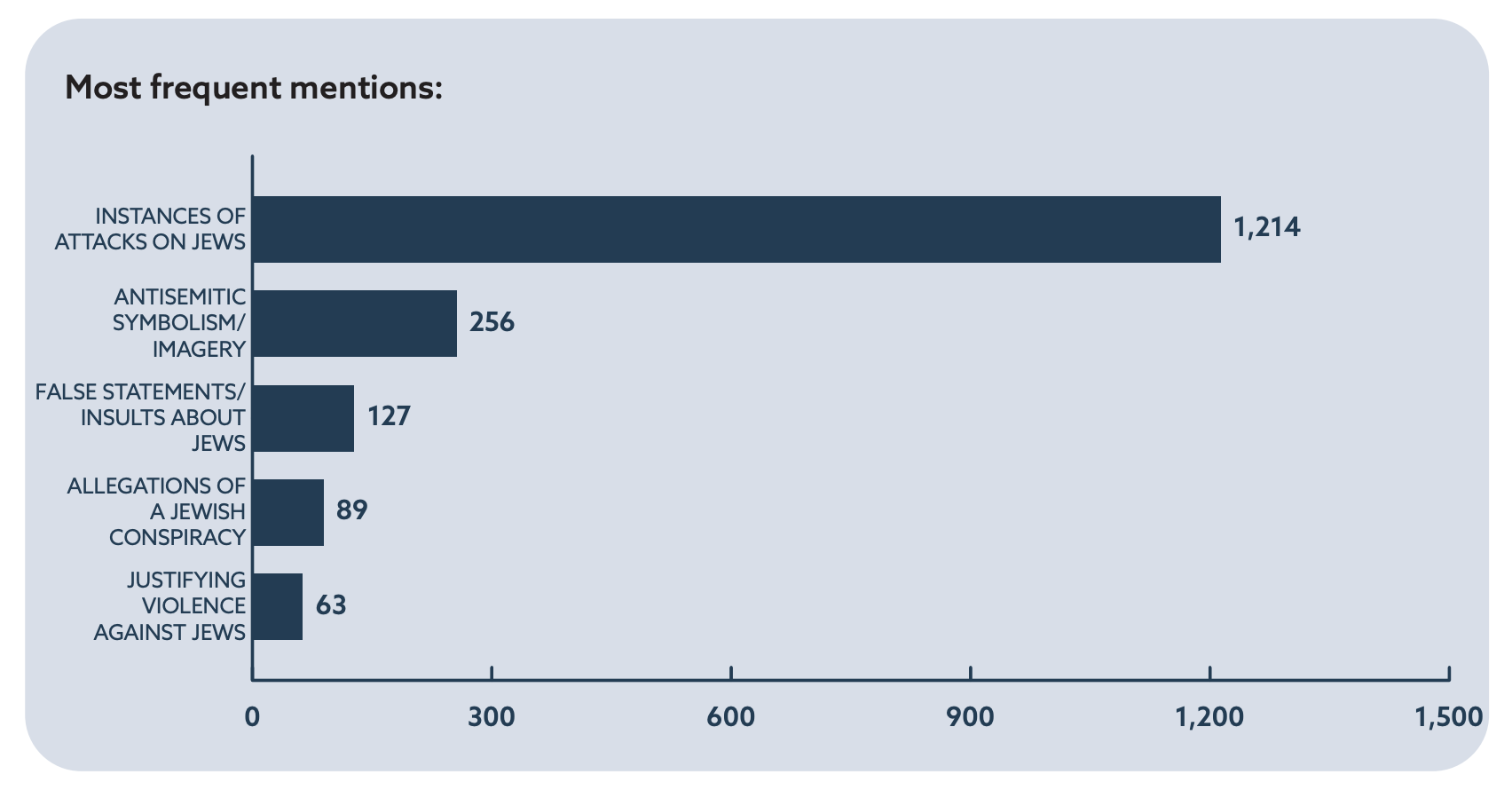

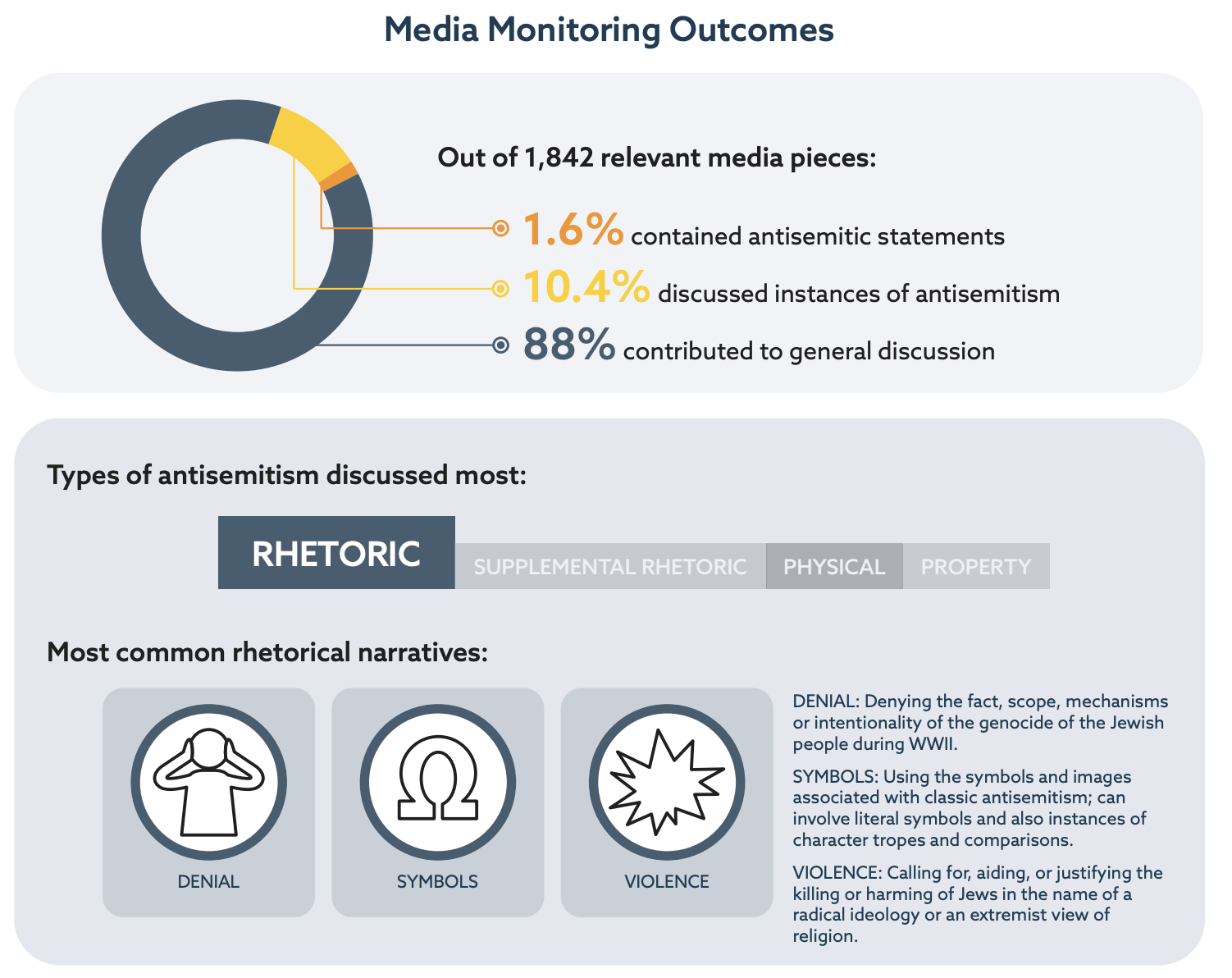

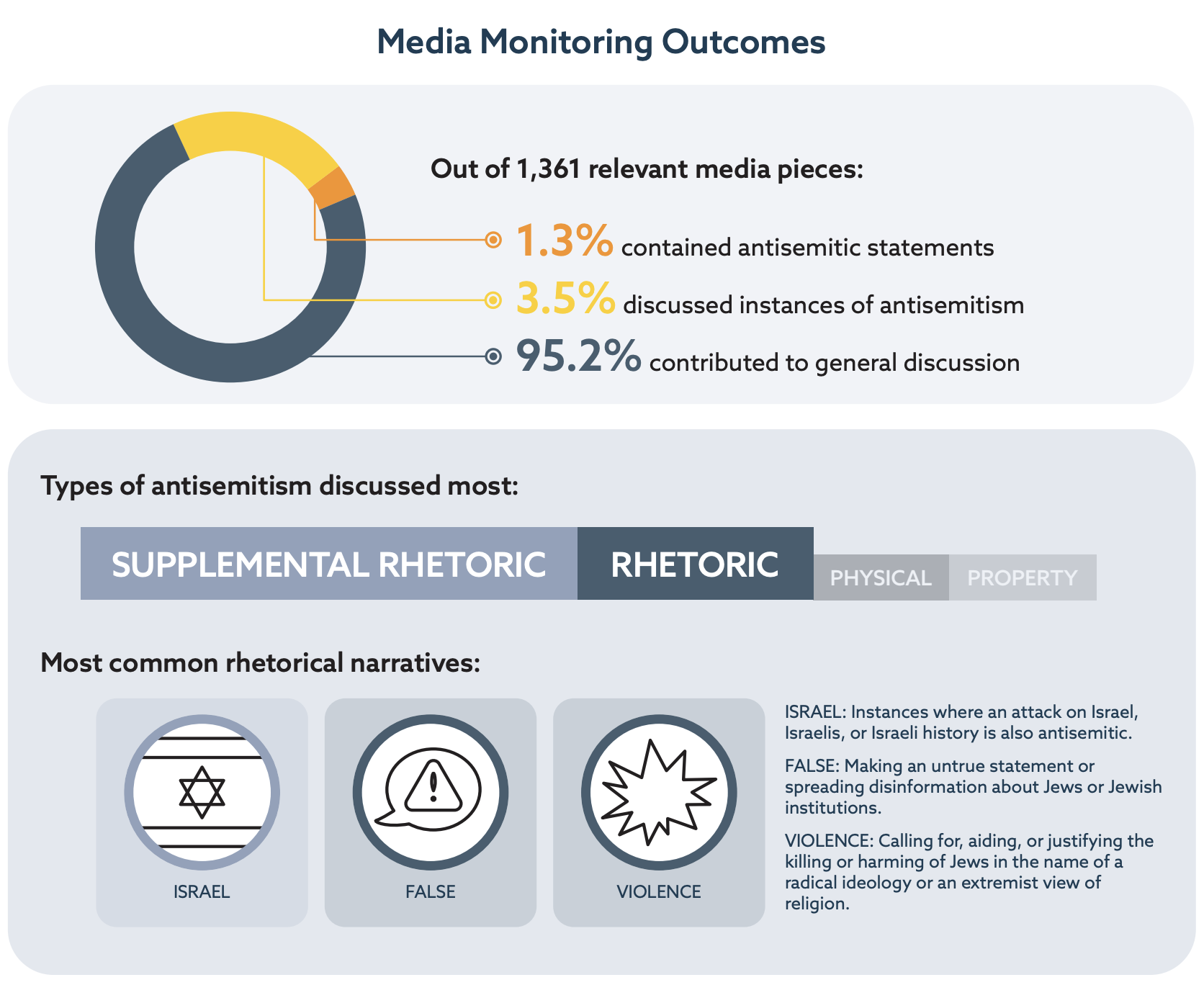

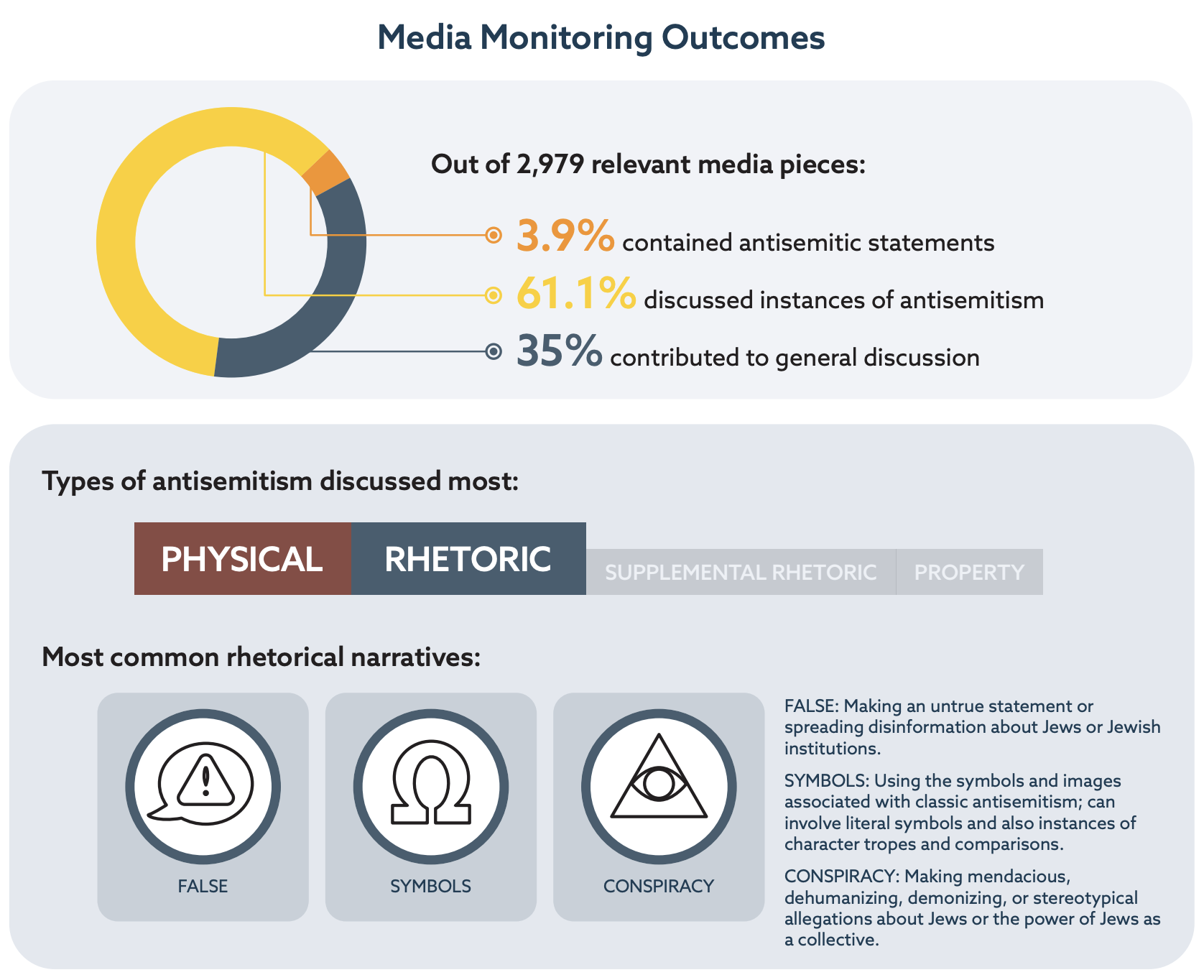

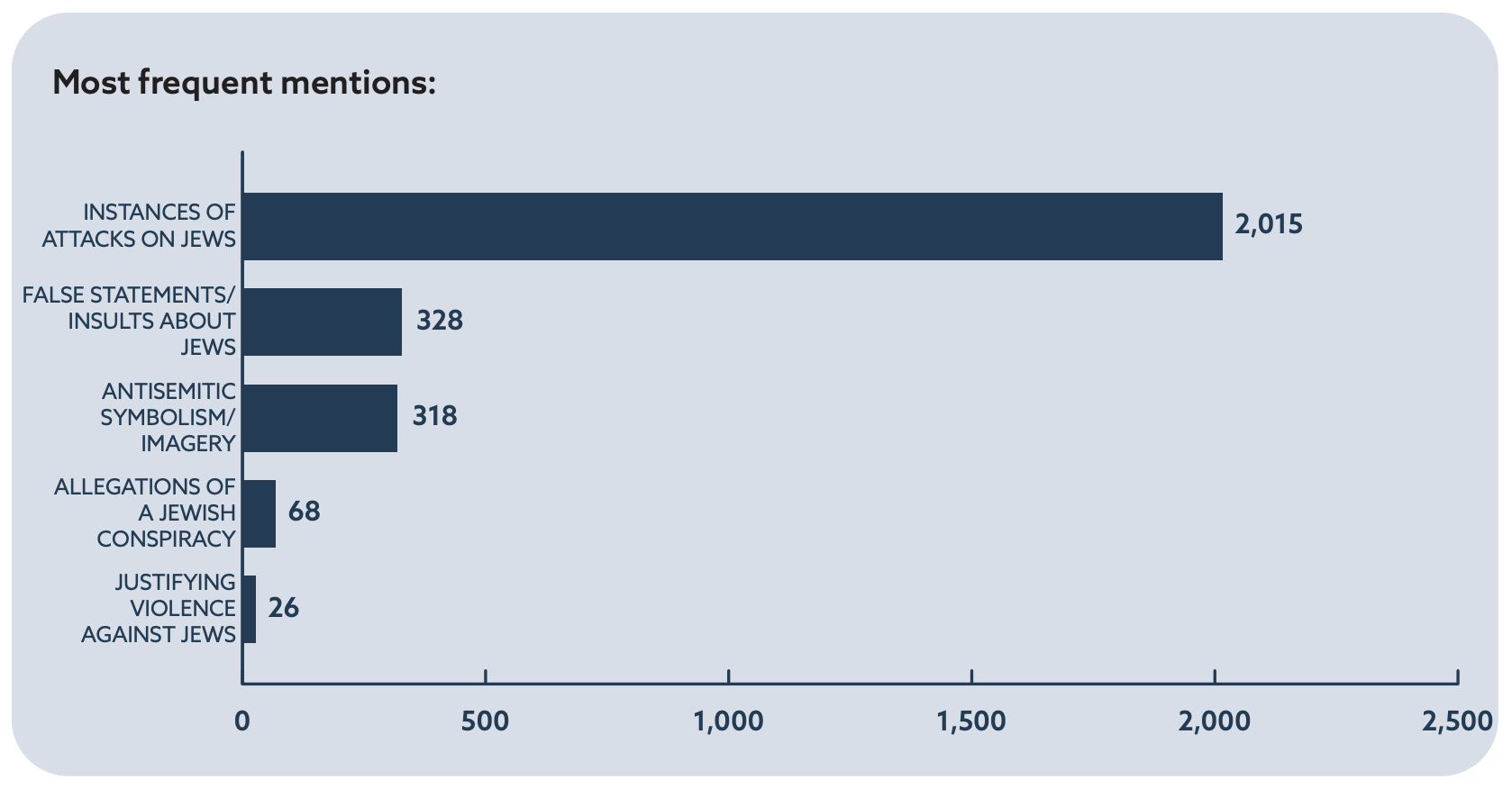

Online media-monitoring results from all seven countries were stored and analyzed in an online dashboard. In total, researchers examined 9,897 relevant search results. Relevant search results are online media pieces — news, discussions, and social media posts — that contained relevant keywords (antisemitism, Israel, Zionist, Holocaust, Jew/s) and belonged to one of the three categories of content described in the Methodology section. Using tags, researchers divided media pieces into three categories: media pieces containing antisemitic language; media pieces presenting news or views on antisemitism in the Western Balkans and beyond; and media pieces contributing to general discussion and news coverage related to the Jewish community worldwide (including the state of Israel).

Out of 9,897 relevant search results, 182 contained implicit forms of antisemitism, and 184 mentions contain explicit antisemitic statements. A total of 4,265 mentions presented news or views on antisemitism in the Western Balkans and beyond, while 5,266 contributed to general discussion and news coverage related to the Jewish community worldwide.

Antisemitic Bias Tags

- A-Explicit: Statements that contain explicit, straightforward, antisemitic rhetoric such as specific swearwords and stereotypes.

- A-Implicit: More complex expressions of antisemitism hidden in the context, such as conspiracy theories.

Rhetoric Tags

- Violence: Calling for, aiding, or justifying the killing or harming of Jews in the name of a radical ideology or an extremist view of religion. This tag is used in situations where extreme rhetoric is used in relation to or in support of violent attacks, regardless of whether those violent attacks have yet occurred.

- False: Making an untrue statement or spreading disinformation about Jews or Jewish institutions. These antisemitic attacks include instances of slander or libel made toward a Jewish figure or institution, but also slander or libel toward a non-Jew if it is based on a premise that involves Judaism or Jews. Examples of how these statements may appear include, but are not limited to, statements that take away credibility from a Jewish figure, malicious rumors, etc.

- Conspiracy: Making mendacious, dehumanizing, demonizing, or stereotypical allegations about Jews or the power of Jews as a collective — especially, but not exclusively, the myths of a world Jewish conspiracy or of Jews controlling the media, economy, government, or other societal institutions.

- Accusation: Scapegoat rhetoric accusing Jews as a people of being responsible for real or imagined wrongdoing committed by a single Jewish person or group, or even for acts committed by non-Jews.

- Denial: Denying the fact, scope, mechanisms (e.g., gas chambers), or intentionality of the genocide of the Jewish people at the hands of Nazi Germany and its supporters and accomplices during World War II (the Holocaust).

- Symbols: Using the symbols and images associated with classic antisemitism (e.g., claims of Jews killing Jesus or blood libel). While this tag may apply to antisemitic attacks that involve literal symbols (such as vandalism of a synagogue with Nazi symbols), it may also apply to instances of character tropes, comparisons made between someone and a Jewish biblical character, antisemitic references, or comparisons to historical Jewish figures or historical events involving Jews.

Supplemental Rhetoric Tags

- AS–Public Figure: Antisemitic instances involved in speech or writing from a public figure or prominent institution or company. For example, a politician who makes a speech that accuses a Jewish population of accelerating the spread of a disease may be tagged with Accusation and AS-Public Figure.

- AS–Virtual Forum: Antisemitic speech or writing that exists and was developed on virtual forums such as those on Facebook, Twitter, or other online communities. This tag is used when an article, discussion, or comment cites a virtual forum as the source or motivation for its antisemitic attack. For example, a discussion thread propagating antisemitic conspiracy theories would be tagged with Conspiracy and AS-Virtual Forum.

- AS–Israel: In instances where an attack on Israel, Israelis, or Israeli history is also antisemitic, this supplemental tag will be used. Because statements made regarding Israel are not inherently antisemitic, this tag will only be used in instances of anti-Zionist and antisemitic attacks.

Physical Tag

- Physical: A physical attack carried out because of the victim’s actual or perceived Jewish identity.

Property Tag

- IND–Property: There are two main categories:

- First, any case in which an antisemitic slogan or symbol is used to damage or vandalize individual property, regardless of whether the property concerned is affiliated with a Jewish individual. Example: Antisemitic slurs painted onto someone’s car, even if the car is not owned by a Jewish person or the attacker had no way to know or believe that it was owned by a Jewish person.

- Second, an action or expression of hostility manifested in the selection of a target such as a Jewish person’s home or individual property. Example: An act of arson committed against a Jewish person’s home, if there is reason to believe that the arsonist knew the homeowner was Jewish and was motivated by that knowledge.

- INST-Property: There are two main categories:

- First, any case in which an antisemitic slogan or symbol is used to damage and vandalize institutional property, regardless of whether the property concerned is affiliated with a Jewish community or is a Jewish institution. Example: A public library’s website is hacked and made to display antisemitic conspiracies. The public library has no direct affiliation with a Jewish community but perhaps was chosen because a large number of people visit its website.

- Second, an action or expression of hostility manifested in the selection of a target, such as a Jewish school or synagogue. Example: Someone smashes the windows of a store that sells only items used for studying or practicing Judaism.

Jews and Western Balkans Societies

The Western Balkans is a political neologism coined in the 1990s to refer to the territory of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, namely its former republics Croatia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia and the former autonomous province of Kosovo. The former Yugoslav republic of Slovenia is excluded, but Albania is added as the term broadly reflects the common aspirations and shared perspectives of these seven states to join the European Union.

Jewish Settlement in the Western Balkans

Jews inhabited the Balkans through successive waves of settlement. While some settled in the Balkans during ancient Roman times (the so-called Romaniots in some areas of present-day Greece, Albania and North Macedonia), most arrived in the 15th century and after, when the Sephardi Jews, expelled from Spain and Portugal, settled in what was then the Ottoman Empire (today’s Western Balkan territories of Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Albania and parts of Croatia). The Ottomans welcomed them as artisans and traders to boost their economy and practiced a particular kind of limited toleration of Jews and majority Christian population as the so-called peoples of the book. Over subsequent centuries, the Sephardim integrated and shared in the urban fabric of Ottoman society and culture while still retaining their distinct faith and language (Ladino or Judeo-Spanish).

The German and Hungarian speaking Ashkenazi Jews began taking up residence in the northern areas of the Balkans (Croatia and today’s Serbian northern province of Vojvodina) by the end of the 18th century, as the Habsburg Empire appropriated the territories from the Ottomans. The biggest influx occurred after the so-called Anschluss or the Agreement of 1867, which cemented the Empire as a complex state called Austria-Hungary. In fact, a great majority of Jews migrated from German-speaking Ashkenazi communities in Hungary to Croatia only a few decades prior to World War I. Some of the early Ashkenazi settlers engaged in lumber or agricultural production and trade from the lands of the local, often foreign nobility, thus sharing in the negative perception of the exploited peasant population. Others engaged in liberal, educated professions, but were nevertheless often perceived with suspicion and seen as “German” or “Hungarian” by the local, predominantly Slavic population. A similar scenario unfolded in Bosnia and Herzegovina after it was occupied by Austria-Hungary in 1878, when thousands of Ashkenazim moved in to find jobs in imperial administration or new business opportunities. They too encountered a different reaction from the local ethnic populations compared to that enjoyed by local Sephardi communities, a distinction which continued well into the interwar period, when the Ashkenazim were still sometimes negatively viewed in comparison to the well-integrated Sephardim.

After Serbia gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878, the local Sephardi Jews were legally emancipated and integrated well into the small urban part of Serbian society. By World War I most Belgrade Jews spoke Serbian, as well as Ladino, sent their children to Serbian schools, and participated actively in public life. During the same period, most descendants of Ashkenazi settlers in Croatia similarly assimilated linguistically and economically and integrated into Croatian society, with the Zagreb community eventually becoming the largest Jewish community of the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, or Yugoslavia, in 1918. The Sephardim of the other territories, which remained under Ottoman rule until 1912, were generally poorer and less integrated than their Sephardic brethren in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Jews who lived in the territories comprising present day Albania, Kosovo and Northern Macedonia spoke almost exclusively Ladino and gravitated, both culturally and economically, to (by then Greek) Thessaloniki.17 Albanian nationalists came mainly from Catholic circles among Albanian speakers and were neither legally nor economically subordinate to Ottomans in the same manner as those living in other Orthodox parts of the Western Balkans. Therefore, the establishment of the first independent state structures in Albania was less accompanied by negative views of Jews as proteges of Muslims as in Thessaloniki and some other parts of the Balkans, which were longer under the Ottomans.18 On the Adriatic coast (now Croatia), the Sephardic communities, settled since the times of Venetian rule, spoke Italian rather than Ladino and were closer to Jewish communities in Italy. In the former areas of southern Hungary (now the northern Vojvodina province of Serbia), Jews spoke Hungarian and often completely assimilated into the Hungarian nation, except for the few Orthodox Jewish communities. In terms of religious practice, most Yugoslav Ashkenazim were Neologs19, whereas most of the Sephardim throughout the Western Balkans were pre-Reform Jews.

Throughout the interwar period, Jews were transforming into a more self-aware minority that kept their own religious, as well as social and political, representation, while also accepting the national identity of the majority society through acculturation and language integration. A vast majority adopted Serbian/Croatian as their language. Time and again the Jewish leadership expressed their loyalty to the king and Yugoslavia, praising them for the relative absence of antisemitism.20 The Law on Religious community of Jews in Yugoslavia, passed on December 13, 1929, was a major historical breakthrough in formalizing full equality for Jews and spurring a significant increase in the activities of most communities in the country.21 The curriculum of Jewish religious instruction widened to include study of the customs, history and language of the Jews and was successfully managed by the Union of Jewish Religious Communities of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in Belgrade, the leading body recognized by the state and the Constitution. This union was also responsible for electing the Great Rabbi, who enjoyed the same rights and honors as all other chiefs of religious communities. There was even speculation that Yugoslavia, like fascist Italy, was interested in the mandate for Palestine based on its exceptionally good rapport with its Jewish citizens and its support for the Zionist project and Balfour Declaration.

According to the last pre-war census (1931) conducted in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the region comprised over half a million ethnic Germans and only 68,405 Jews (39,010 Ashkenazim, 26,168, Sephardim, and 3,227 Orthodox in six smaller Hungarian speaking communities in the north). Accounting for the several hundred who acquired citizenship each year and increased rates of immigrants (including refugees), population estimates range close to 80,000 Jews on the eve of World War II, making up half a percent of Yugoslavia’s 15.5 million total population. In terms of languages used, occupations, wealth, integration and political views, the Yugoslav Jewry reflected, if not superseded, Yugoslav diversity. The largest communities were in Zagreb (10,000), Belgrade (10,000) and Sarajevo (9,000), representing 6.5 percent, 3.5 percent and 10.5 percent of the population, respectively. In terms of socio-economic structure, most Jews were middle class, with few rich individuals. Some destitute Jewish communities existed, especially in southern region of Macedonia. They held a variety of occupations, with almost 40 percent employed as merchants, 25 percent as state employees, around 13 percent as artisans and 8 percent as belonging to liberal, educated professions. Jews were especially well-represented among lawyers and doctors.22 Yet there was a notable difference in wealth and occupations between Sephardim in formerSerbian and Ottoman territories, who were much poorer than Ashkenazim in former Austro-Hungarian provinces, most of whom belonged to middle and higher classes and excelled in trade.

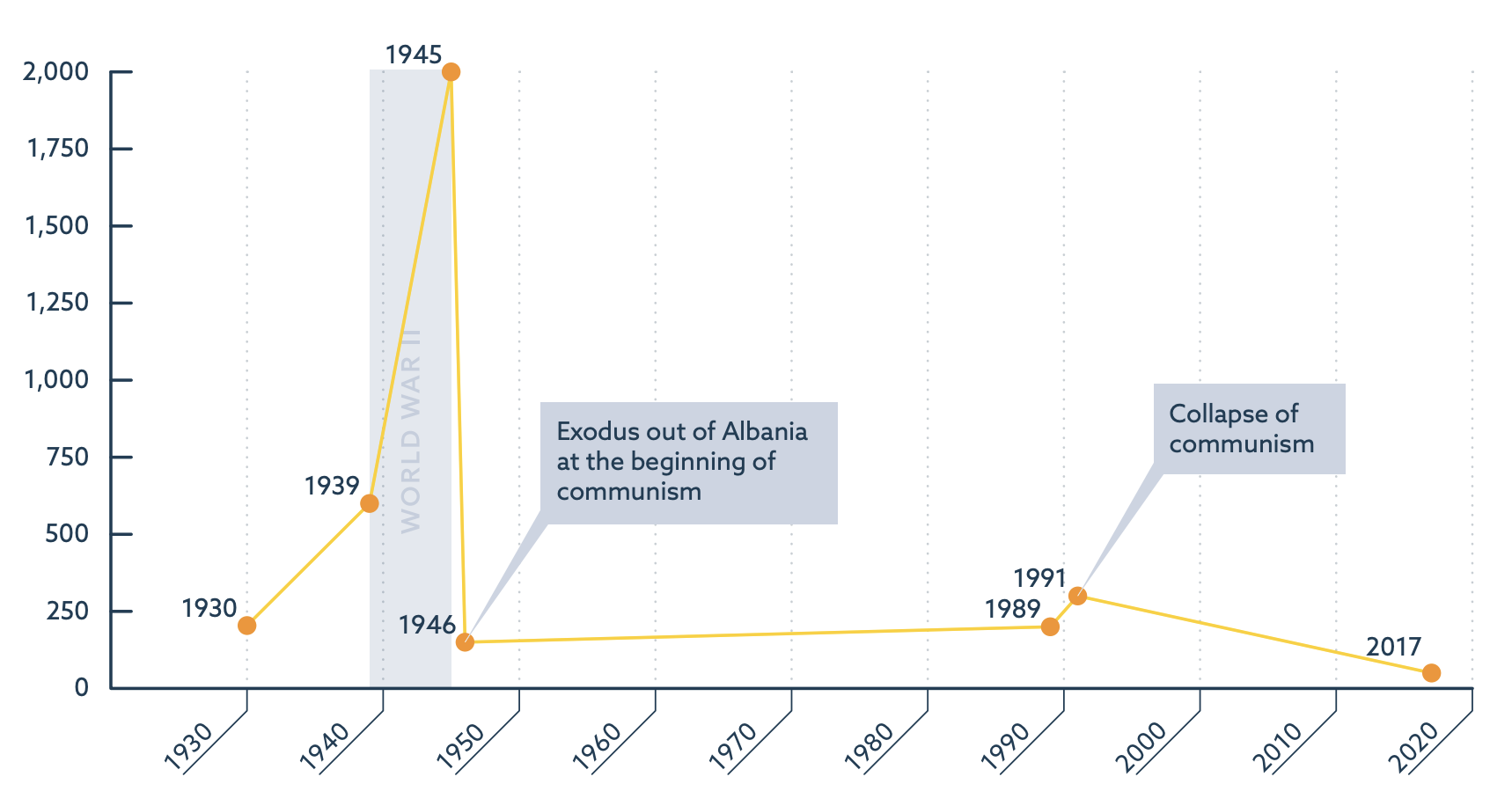

Interwar Yugoslav Jews with different traditions, languages and customs, could hardly develop a common Zionist ground. The degree and type of participation of Yugoslav Jews in the Zionist movement differed from region to region. The Sephardim of Bitola (Ottoman Monastir) in modern-day North Macedonia and some in Kosovo fell in deep poverty once separated from their metropolis of Thessaloniki and were most likely to emigrate, be it to Palestine or elsewhere, but not very active in the Movement. On the other hand, the Ashkenazim of Croatia, and especially Zagreb, were the most active Zionists, but less likely to go to Palestine. Despite activities for the preparation of the halutzim, the pioneers who would eventually emigrate to Palestine, the mostly silent majority of Jews in Yugoslavia, even the young Zionists well until the late 1930s, had no such ambition.23 Furthermore, the near absence of antisemitism in that period did not foster cohesive ideology among Jews. Jews were legally emancipated and Yugoslav authorities did, more often than not, intervene in their favor. Instead of Aliyah, most Jews, especially among the Sephardim, argued for much stronger integration within Yugoslav society. It was only in the 1930s that the Yugoslav Jewry finally became united and members of both Ashkenazi and Sephardi communities frequently began intermarrying, mostly due to antisemitic hysteria spreading from Germany and causing the massive flight of Central European Jews to and via Yugoslavia and later Albania.24 According to the Albanian census of 1930, there were only 204 Jews registered at that time in Albania, but they were nevertheless granted official recognition as a community in 1937. By the beginning of the war, the number of Jews swelled close to one thousand, due to a number of German and Austrian Jews taking refuge in Albania.

Antisemitism and the Holocaust in the Western Balkans

Compared to other European countries, antisemitism in the Balkans was considered to be rather marginal. An early sign of antisemitism in Yugoslavia may have emerged in response to the mass migration of Polish Jews in the mid-1920s. The arrival of thousands of Jewish refugees from 1933 revived the issue with many reactions, mainstreaming antisemitism in the public. Nevertheless, until 1938 Yugoslavia overall remained exceptionally welcoming to Jewish refugees. Even after restrictions were imposed in 1938, the Yugoslav borders remained porous.25 However, Nazi propaganda turned powerful German minority organizations in Yugoslavia, such as the Kulturbund, into important vehicles of antisemitism. In addition to general antisemitic tropes, the Kulturbund clearly identified Jews with the Yugoslav regime and its ruling ideology.26 Due to their support of the Yugoslav government, Jews in Croatia also became an easy target for radicalized Croatian nationalists, associated with the Ustaša organization, who in the 1930s increasingly looked to Nazi Germany for ideas and support and eventually embraced antisemitism. On the other hand, some Serbian nationalist circles connected Jews with the Croatian national project, envious of Zagreb’s development into the biggest industrial and commercial center in Yugoslavia, with its Jewish bourgeoisie playing a significant role. Other antisemitic agents included the Russian emigrant church; “Zbor,” a small far-right movement that attracted Yugoslav nationalists; and the leader of the Slovenian clerical party, Pater Anton Korošec, who was especially influential as the Minister of the Interior introducing restrictions to Jews.27 In this atmosphere of rising antisemitism, and under the influence of Jerusalem Mufti Haj Amin el-Husseini and the conflict over Palestine, anti-Zionist and anti-Jewish texts also circulated among Bosnian Muslims just prior to the war.28 Albania seemed the only place spared of this wave of antisemitism emerging from Germany and Central Europe due to the historic isolation of the country, which led to few people understanding the motives of antisemitism.29

By early 1940, the continuous stream of refugees made the aid model led by the Union of Yugoslav Jewish Religious Communities unsustainable. The government passed decrees about internment and prohibited the movement of refugees. For those interned under these measures, the Jewish community accepted the responsibility for establishing and managing its own centers to avoid anything resembling concentration camps. Yet nothing prepared the state or the Jewish community for the emergency that became known as the so-called Kladovo transport, which saw over 1,000 mostly Austrian Jews forced to live on three boats on the Danube. While they were eventually moved to better conditions in Šabac, a majority remained trapped in Yugoslavia and were among the first victims of Nazi executions. On October 5, 1940, under pressure from Nazi Germany, Yugloslavia’s seriously divided government passed two anti-Jewish laws in the form of decrees. There was a limit set on the number of Jews enrolled in secondary schools and universities and Jews were excluded from wholesale trading in food items.30 The Jewish community and most of the public reacted with fury. As such, there was little application of these laws before Yugoslavia was invaded. A vast majority of Jews remained in the country, refusing to believe that a fate similar to the Jews of Germany and other countries could ever befall them.

After the invasion and partition of Yugoslavia in April 1941, Germany established a military occupation in Serbia and later installed a puppet Serb civil administration. During the late summer and autumn of 1941 in order to quell an uprising, German military and police units shot male Jews from Serbia and Banat (approximately 8,000 people) in addition to thousands of Serbs and Roma.31 Jewish women and children were incarcerated in the Zemun/Staro Sajmište concentration camp. Between March and May 1942, German Security Service (SS) Police personnel killed around 6,280 people, almost entirely Jews from the Zemun camp. By the summer of 1942, no Jews remained alive in Serbia, unless they had joined the Partisans or were in hiding.

In the so-called Independent State of Croatia (which included Bosnia and Herzegovina), the Ustaša leadership, installed by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, instituted a reign of chaotic terror aiming to establish an ethnically pure Croatian state by exterminating Serbs, Jews and Roma from its territory. In all, the Ustaša killed between 320,000 and 340,000 ethnic Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina between 1941 and 1942, often burning entire villages, torturing men and raping women. By the end of 1941, Ustaša had incarcerated over 20,000 Jews from Croatia and Bosnia in camps they set for Serbs, Jews and Roma throughout the country (Jadovno, Kruščica, Loborgrad, Đakovo, Tenje, and the largest one, in Jasenovac), where most perished. In addition, from 1942-1943 Croatian authorities transferred about 7,000 Jews into German custody, who then deported them to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Croat Ustaša were also responsible for the extermination of at least 25,000 Roma men, women and children from Croatia and BosniaHerzegovina.

Elsewhere, in January 1942, Hungarian military units shot over 3,000 people (2,500 Serbs and 600 Jews) in Novi Sad, ostensibly in retaliation for an act of sabotage. Hungary, however, refused to deport Jews from the Yugoslav areas it annexed. After the Germans occupied Hungary in March 1944, Hungarian authorities deported at least 16,000 Yugoslav Jews to AuschwitzBirkenau, where the majority died in the gas chambers. In March 1943, Bulgarian military and police officials arrested and deported the entire Jewish population of Yugoslav Macedonia and Pirot, which was annexed by Bulgaria. More than 7,700 people were sent to the Treblinka concentration camp, with virtually none surviving. In 1944, the SS Skanderberg division, made up of Albanians from Kosovo and the Sandžak region, arrested between 300 and 400 Yugoslav Jews in Kosovo, who were then deported to Bergen-Belsen, where at least 200 are thought to have died. A small faction of Bosnian Muslim nationalists also joined the Axis forces.

Many Jews in Yugoslavia joined the antifascist resistance, the Communist-led Partisans, which was also promoting equality among different Yugoslav peoples. Of the 4,572 Jews who joined the Partisans, 2,897 served in combat units, where 722 lost their lives. Out of 1,569 who served as civilians, mostly as medical staff, 596 died.32 Initially anti-fascist Četniks, who pledged allegiance to the Yugoslav Kingdom and its government in exile, harbored very few Jews and turned into a Serbian nationalist force often engaging in revenge actions and crimes against Croats and Muslims and Communist Partisans. The Četniks and Ustašas were eventually defeated by the Partisans, which also engaged in mass retributions and executions of those deemed the people’s enemy. These ethnic massacres and brutal conflicts during and in the aftermath of World War II characterized the civil war taking place in Yugoslavia in parallel to anti-fascist resistance, which altogether left many scars in the memory of the people.

Generally rejecting or evading German and Ustaša demands to deport Jews from areas under their control, Italian authorities (in Dalmatia and on islands of today’s Croatia, Herzegovina, and Montenegro) and the army saved up to ten thousand Yugoslav and other Jews until Italy’s capitulation on September 8, 1943. Thereafter, most Jews fled to Italy proper or were rescued by the Yugoslav Partisans, where a majority survived. In Albania and Kosovo under Italian occupation, Jews were interned but essentially protected. Hundreds of Yugoslav and Greek Jews survived by escaping to Albania, which as an Italian protectorate also included territories of Kosovo and Western Macedonia. Albanians, regardless of their Christian or Muslim backgrounds, continued to hide and protect mostly Jewish refugees for another year after the occupation of Albania by Nazi forces following the capitulation of Italy. In Albania, saving Jews can be attributed to patriarchal principles of honor and morality, rather than to decisive antifascist or anti-German positions. Even some collaborators with Nazis saved the Jews.33 In this way Albania became the only European nation to emerge from World War II with a higher Jewish population than it had at the war’s beginning.34

The Place of Jews in the Context of Contemporary Balkan Societies

Historically, Jews played a significant social, cultural and economic role in the Balkans, far greater than their small share of the general population would suggest. Before the Holocaust, a vibrant Jewish life existed only in larger cities such as Thessaloniki, Zagreb, Belgrade and Sarajevo, though there were also smaller towns with substantial Jewish populations, like Skopje and Bitola in the south or Osijek, Subotica and Novi Sad to the north. Remarkably, over the centuries Jews in the Balkans faced relatively less discrimination and antisemitism compared to other parts of Europe. All of this changed during World War II, when the vast majority of Jews in the Western Balkans fell victim to the Nazi policy of extermination perpetrated by German occupation forces and aided by a range of Serbian, Bulgarian, Hungarian and Kosovo-Albanian collaborators. In Nazisatellite Croatia, Croat and Bosnian Muslim supporters of the fascist Ustaša initially undertook the extermination of Jews on their own, though later deportations were dictated by Germany. Nevertheless, there is little evidence of pogroms or deliberate anti-Jewish violence in the Balkans based on local Christian and Muslim hatred against Jews or deeply ingrained antisemitism. After the war and the creation of the state of Israel, more than half of the approximately 15,000 Yugoslav Jewish survivors and almost the entire Jewish population of Albania emigrated in several waves. The Federation of Jewish Communities in Yugoslavia, formed in the aftermath of the war, facilitated the process, carefully mediating the Zionist aims within Yugoslavia’s Communist ideological framework. From building communal infrastructure to dedicating monuments to Jewish victims of the Holocaust, the leaders of the Federation of Jewish Communities pushed through a rebuilding agenda that was a part of a wider Yugoslav narrative, and one that defined Jewishness as an identity firmly rooted in the new Yugoslav political project.35 Social activities continued to flourish while religious aspects of society were downplayed. In Albania, communists strongly promoted Marxist ideology and tried to extinguish all religious practices. Yugoslavia’s severing of relations with Israel in the aftermath of the Six Day Arab-Israeli War of 1967 raised tensions but did not contribute to antisemitism as seen in other Communist-led countries, nor did it change the model of survival of Yugoslav Jewish communities.

Beginning in the early 1980s, the region was engulfed by turmoil, first in the form of an economic crisis and then systemic legitimacy struggles, which accompanied inter-ethnic hostilities in Kosovo and then throughout the former Yugoslavia. The strife resulted in the dissolution of Yugoslavia and armed conflicts in Croatia (1991 and then again in 1995), Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992-1995), and Kosovo (1998-1999), with shorter conflicts ensuing in North Macedonia. The Genocide of Serbs in Croatia during World War II, as well as the terrible crimes committed by the Četniks and other armed groups were used during the late 1980s and 1990s to generate hatred and provoke hostilities following the dissolution of Yugoslavia. Even within present-day social media discourse, the derogatory use of the word Četnik for Serbs or Ustaša for Croats are commonly spotted. Thousands of Jews were evacuated from Sarajevo under siege in 1992 and Serbia during the NATO bombing campaign in 1999. Most of them chose to immigrate to Israel and the United States. Albania also saw outbursts of violence in its troubled transition throughout the 1990s and the few remaining Jews left.

While this research does not cover the conflicts of the 1990s, the issue of antisemitism nevertheless came to the fore by the nationalist politics generated or tolerated by the ruling regimes in all Western Balkan societies during this period. Some, such as Croatia’s first president Franjo Tuđman, made antisemitic comments. Others, like the Yugoslav secret services, allegedly attacked Jewish property in Zagreb in order to foment unrest in Croatia. More importantly, the war of words that fueled and accompanied the conflicts during the crisis and in the aftermath of the dissolution of Yugoslavia displayed a common trope or wish to be a Jew or the so-called “Holocaust Envy.”36 In the Western Balkans, Serbs, Slovenes, Croats, Albanians, and Bosnian Muslims all strove in one way or another to position themselves as victims and to compare their fate to that of Holocaust victims, while placing blame on others. These local comparisons were contingent and interlocked with misuses of the Jewish trope in the global media space dominated by the U.S. and Western Europe. The local outbursts of philosemitism, however often laid the groundwork, easily merged or replaced with antisemitic conspiracy theories. In a region relatively devoid of homegrown antisemitism, hatred against Jews has often been imported during the last three decades.

At the same time, all countries covered by this research established diplomatic and other relations with Israel. Most have taken steps towards restitution of Jewish property that was nationalized in 1940s. Actions, some controversial, were taken to research and commemorate the Holocaust, such as the Memorial Centre for the Jews of Macedonia in Skopje. In states that emerged out of the former Yugoslavia, small Jewish communities are persisting in Belgrade, Zagreb, and Sarajevo, among others. In recent years, a Holocaust Memorial and museum were unveiled in Albania that honors Albanians who safeguarded Jews from Nazi persecution during World War II.

Albania

Albania does not have a significant Jewish presence; at the time of this writing, it is estimated that approximately 40 to 50 Jews live in Albania. Jewish heritage, history, and connections with Albania are memorialized in various forms, such as museums, memorials, conferences, publications, documentaries, and public events. Albania prides itself on being a country free of antisemitic sentiment and discrimination against Jews. Generally, the legal framework dealing with racism in Albania is in line with European and international standards. The legislation states that race-based discrimination is unlawful but has no specific reference to antisemitism. Still, countering antisemitism and hate-speech awareness-raising campaigns have become more frequent, mainly initiated by civil society organizations with international donor support. In addition, Albania formally adopted the IHRA’s definition of antisemitism in October 2020, with a unanimous vote in parliament.37

There is a long history of Albanian political actors promoting a “rescue narrative” that celebrates, and to some extent idealizes, the actions Albanians took during World War II to protect Jews. Moreover, many political representatives often link this narrative with the narrative about excellent state relations between Albania and Israel to suggest that good bilateral relations serve as evidence of a minimal presence of antisemitism in Albania. Albanian media generally reflect narratives of historic friendships between Albanians and Jews and excellent bilateral relations between them with its selection of news coverage. Consequently, media coverage (not only in this media monitoring) pays significant attention to mutual state visits, the commemoration of the Holocaust and the protection of Jews in Albania during World War II, Israeli investments in Albania in various sectors, and the history of Jews overall. This trend was even more visible in 2019–2020, due to events that strengthened bilateral relations between the two countries, such as humanitarian help during an earthquake in Albania in 2019, the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, and Albania’s adoption of the IHRA definition of antisemitism in 2020 This report’s media monitoring indicated that antisemitism or antisemitic narratives are uncommon in Albania. Instead, the overarching narrative present in the society and spotted during the media monitoring is that “Albanians and Jews have a long history of friendship, and in the last three decades, the Albanian and Israeli states enjoy excellent relations.” The narrative in which Albanians portray themselves as rescuers of Jews with a high sense of humanity, tolerance, and a long tradition of hospitality is deeply rooted in Albanian society and often used by the political representatives to increase the prestige of the country in the eyes of Albanians as well as foreign actors.

In some cases, the media refers to occurrences of antisemitism abroad, most often related to Holocaust remembrance. However, some new fringe online media and social media accounts of particular individuals and public figures produce antisemitic narratives. These have not become mainstream and remain marginal to the overall public discourse and agenda-setting. The media monitoring found traces of rhetorical antisemitism, primarily through conspiracy theories regarding Jewish people controlling the world order and economy and, most frequently, about Hungarian philanthropist George Soros’s impact on Albanian political developments. The link between the conspiracy narrative and hate speech against George Soros, and allegations about Jews and their power as a collective is not always self-evident. AntiSoros rhetoric exacerbates the antagonism between left and right political actors in Albania, their allies, and their supporters. It also aggravates the existing vulnerability of average citizens to disinformation and conspiracy theories.

Moreover, several studies described later in this report point to a resurgence of radical Islamic groups and an emergence of informal extremist groups. The radicalization of youth by fundamentalist religious groups and violent extremists has become a cause for concern in Albania. This could create a breeding ground for antisemitism, which has not historically and culturally been part of Albanian society but could now be imported from abroad, particularly in the online media landscape.

Historical Overview

While there is a long history of Jewish settlement in Albania, their numerical presence was rather marginal. Nowadays, Jews in Albania are mostly known and referred to as refugees who escaped to Albania before and during World War II. Almost all of them survived, thanks to Italian occupation authorities until 1943 and the Albanian collaborationist authorities and common Albanians thereafter. The Albanian government protected Jews by providing them with identity documents and not handing them over Nazi German occupiers.38 More importantly, Albanian people of all backgrounds hid and rescued hundreds of Jews. There are various interpretations of this rescue. Some survivors claimed that antisemitism was simply non-existent, as many Albanians did not know anything about Jews and rescued them as they would rescue any vulnerable human being. In a traditional society, solidarity and care for those in danger are simply customary. Others interpreted it as a particular feature of Albanian patriarchal society regulated by the custom law, known as Kanun. The Kanun protects the guests, and this protection is extended to Jews. A promise made to uphold the Kanun is a so-called besa. So, whoever is offered a besa is entitled to protection.39 Finally, the religious pluralism of the Albanians created a society more tolerant of both native and refugee Jews.

Given the extreme nature and isolation of Albania under Communist rule, the details about the rescue of Jews during World War II emerged fully only in the 1990s and have been confirmed by Yad Vashem awards of “Righteous among nations,” and numerous reports and publications. Since then, the rescue has been commemorated in Albania, and a very friendly relationship established between Albania and Israel. However, recent phenomena such as radical and fundamentalist Islamist groups and extreme nationalist ideology craving a so-called “Greater Albania” risk jeopardizing the legacy of tolerance and solidarity of the Albanians.

Kanun refers to a set of customary oral laws developed over centuries. It states that the household belongs to God and the guests. Besa is the Albanian sworn oath to keep a promise at any cost.

The Jewish Minority in Albania Today

According to the World Jewish Congress, as of 2017 up to 50 Jews live in Albania, out of an overall population of 2.87 million. A synagogue was opened in Tirana in 2010, where a Holocaust memorial was also unveiled in July 2020 to honor the victims and the Albanians who protected Jews from the Nazis.40 The inscription of the memorial is written in three languages — English, Hebrew, and Albanian — and reads, “they risked their lives to protect and save the Jews.”41 The Holocaust is taught in European history modules in higher education and history courses in pre-university education. The history of Jews in Albania is preserved in cultural institutions, such as the Solomon Museum in Berat, which opened in 2018 and features photos and stories of Jewish history in Albania from the past 500 years. The National Museum in Tirana features an exhibit on Jewish history as well. Additionally, the Ministry of Culture opened the National Museum of Jews in Vlora in July 2020, a project initiated by the Albanian American Development Foundation.42 Additionally, Israel Today is an online portal with a mission to provide information for the Jewish community in Albania and Kosovo.

The historical ties between Jews and Albanians and the good relations between Albania and Israel can also be noted in the fact that Albania is producing historical studies and other cultural products like documentaries and museums about the Holocaust and the Jewish experience in Albania, even though Jews are almost absent in the country. University of Tirana Professor Dr. Tonin Gurjarj explained that “Albania has perpetuated its friendship with Israel through symbols such as the naming of streets (Jewish Street in Berat and Vlora), as well as the Holocaust commemoration every January 27 by the Albanian Parliament, the establishment of museums for the history of Jews in Albania, high-level conferences, publications and through continuous exchanges between the two nations.”43 Also, the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem has honored 69 Albanians as “Righteous Among the Nations,” an honor bestowed upon people who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust.44

Good relations between Albania and Israel were also evidenced during the devastating earthquake that hit Albania on November 26, 2019. According to some estimates, more than 1,500 Albanian families are now able to return to their homes after Israeli support to reconstruct not only apartments but also hospitals and schools hit by the earthquake.45 Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu posted a video of Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama thanking the Israeli team for its help in the postearthquake emergency, and thus reaffirmed Israel’s support for Albania during difficult times.46 Bilateral relations are also positively reflected in Albanian media.

As discussed earlier, the rescue of Jews in Albania during the Nazi occupation is usually explained by the besa cultural code. Another explanation, put forward by the historian Shaban Sinani, holds that other principles, such as solidarity and looking out for others — which are even more important in times of war — should be considered.47 He also cites other factors, such as the size of the Jewish population in Albania, which was small and therefore easy to assimilate, and the fact that as a Muslim-majority country Albania did not have a history of Christian antisemitism.48

Another explanation is that, due to Albania’s ruling religion’s changes over the centuries, Albanian society was primarily formed based on ethnicity, and there has been a peaceful cohabitation of various religions in the country. Professor Ferit Duka argues that this tolerance dates to late antiquity (5th–6th century), when a chapel in the city of Saranda (then known as Onhezmi), was used as both a synagogue and a church.49 He further notes that “for us historians this fact has a two-folded significance: it shows that cohabitation and tolerance between two religions bear testimony to the presence of Jews in Albania since antiquity.”50 The combination of such factors — cultural codes such as loyalty and honor-keeping, solidarity with those in need, the prevalence of ethnicity over religion, cohabitation, and tolerance among many different religions — could have a beneficial impact on the level of antisemitism in Albanian society. However, recent phenomena, such as radical and fundamentalist religious groups and extreme-right ideologies, risk jeopardizing this tradition.

After the fall of the Communist regime, Albania reinstated freedom of religion, which the Communist government had banned by law in 1967. Since then, Albania has seen a resurgence of religions, including the formation of some radical groups.51 For instance, a recent report found that most Albanian jihadis have come into contact with the Salafist branch of Islam, which took root in Albania during the 1990s via several Islamic humanitarian organizations that served as cover for international terrorist networks.52 Fundamentalist Salafism’s influence has spread more dramatically in the last decade, fed in part by the dire economic and social situation in the region and the general lack of opportunities, especially for youth.53 Although crackdowns by security forces and54 Albanian Muslims are moderate and radical interpretations of Islam are rare, there is still the risk of it becoming the breeding ground for religious radical and violent extremism.55 Some antisemitic sentiments have emerged,56 but they are not accepted by the Muslim clergy, who argue that “Islam in Albania is entirely compatible with human rights and democracy.”57 The strictly secular Albanian state, which distances itself from grassroots religious movements, has made these communities susceptible to foreign influence. This poses a risk of importing antisemitism from abroad, even though it is not historically or culturally part of Albania.

Although studies show that there are few organizations with extreme-right ideologies and programs in Albania, there are individuals who sympathize with far-right ideologies. Certain groups, political actors, and subcultures endorse at least part of such doctrines.58 Nevertheless, as indicated in Arlinda Rrustemi’s research on extreme-right ideologies in southeast Europe, Albania seems to be the Western Balkan country least affected by far-right trends and ideologies.59 However, this situation could soon change, as the narrative of “Greater Albania” builds up tensions with neighbors in the region and is likely to feed far-right tendencies. While there are hardly any organizations with fascist or Nazi heritage or ideological ties currently present in Albania, scholars argue that the general rise of the far-right in Europe, the increase of populism and populist contenders in Albania, immigration from Syria and other conflict areas, the difficult economic situation, and the ongoing political crisis could lead to the emergence of extreme-right groups.60

A more immediate risk is antisemitism imported by radical Islamist groups with links to the Middle East, as the influence of these groups in spreading antisemitism is not sufficiently monitored by Albanian authorities.

Legal and Institutional Provisions

Legal Protection and Legal Gaps

Non-discrimination principles are set out in the Constitution of Albania (Article 18). The Albanian labor code, criminal code, and Law on Protection from Discrimination (LPD) are in line with E.U. anti-discrimination directives. Article 265 of the criminal code concerns the promotion of hatred or strife. The LPD partly prohibits discrimination based on a perception or assumption of a person’s characteristics. While it doesn’t address such, the LPD partly prohibits discrimination based on a perception or assumption of a person’s characteristics. While it doesn’t address such discrimination explicity, Article 3(4) of the LPD includes a prohibition against “discrimination because of association” with persons who belong to groups mentioned in Article 1 or “because of a supposition of such an association.”

Other key legislation includes the Administrative Procedure Code, Criminal Justice Code for Juveniles, Law on the Protection of National Minorities, Law on the Organisation and Functioning of the Prosecutor, etc. Article 24(1) and (2) of the constitution safeguard freedom of conscience and religion, including an individual’s right to choose or change their religion or faith. The LPD has a similar provision regarding protection from discrimination on the grounds of religious beliefs. Under Article 10 on “Conscience and religion,” discrimination is prohibited in connection with the exercise of freedom of conscience and religion, “especially when it has to do with their expression individually or collectively, in public or private life, through worship, education, practices or the performance of rites.”

Under Article 10, discrimination is prohibited in connection with the exercise of freedom of conscience and religion.

Politicians in Albania produce and spread most of the hate speech in the media, though journalists, media commentators, and opinion makers are also to blame.61 Public debates in Albania are not immune to hate speech — particularly against LGBTQI+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex) communities, Roma communities, and religious groups — and this is considered acceptable for the most part. A wave of Islamophobic sentiments and narratives has been observed in Albania, with hate-speech posts on social media and public television debates.62 Such cases have recently been marked in the parliament, as well. However, public condemnation of hate speech by high-ranking political or other public figures is rare. Usually, it is civil society and academics who react to, or counter cases of hate speech.

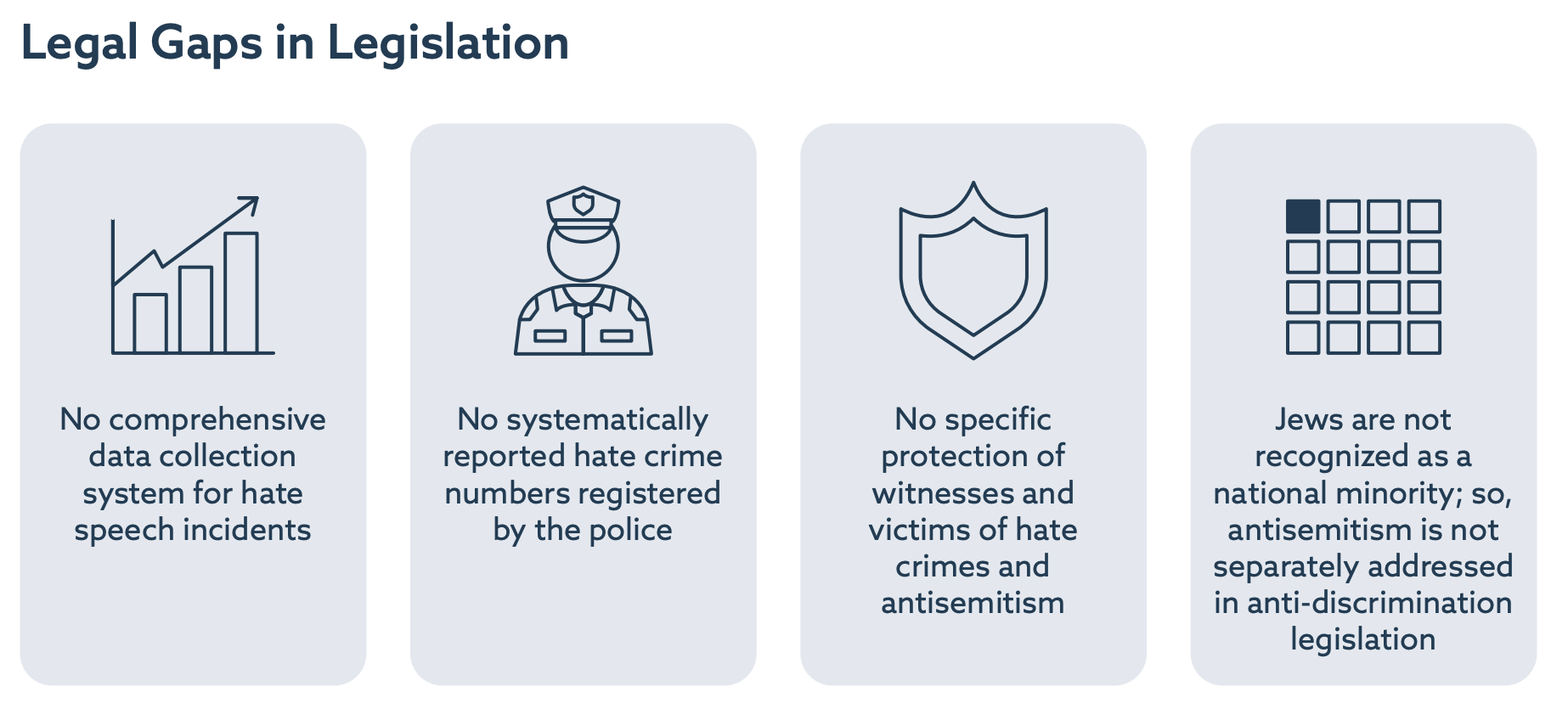

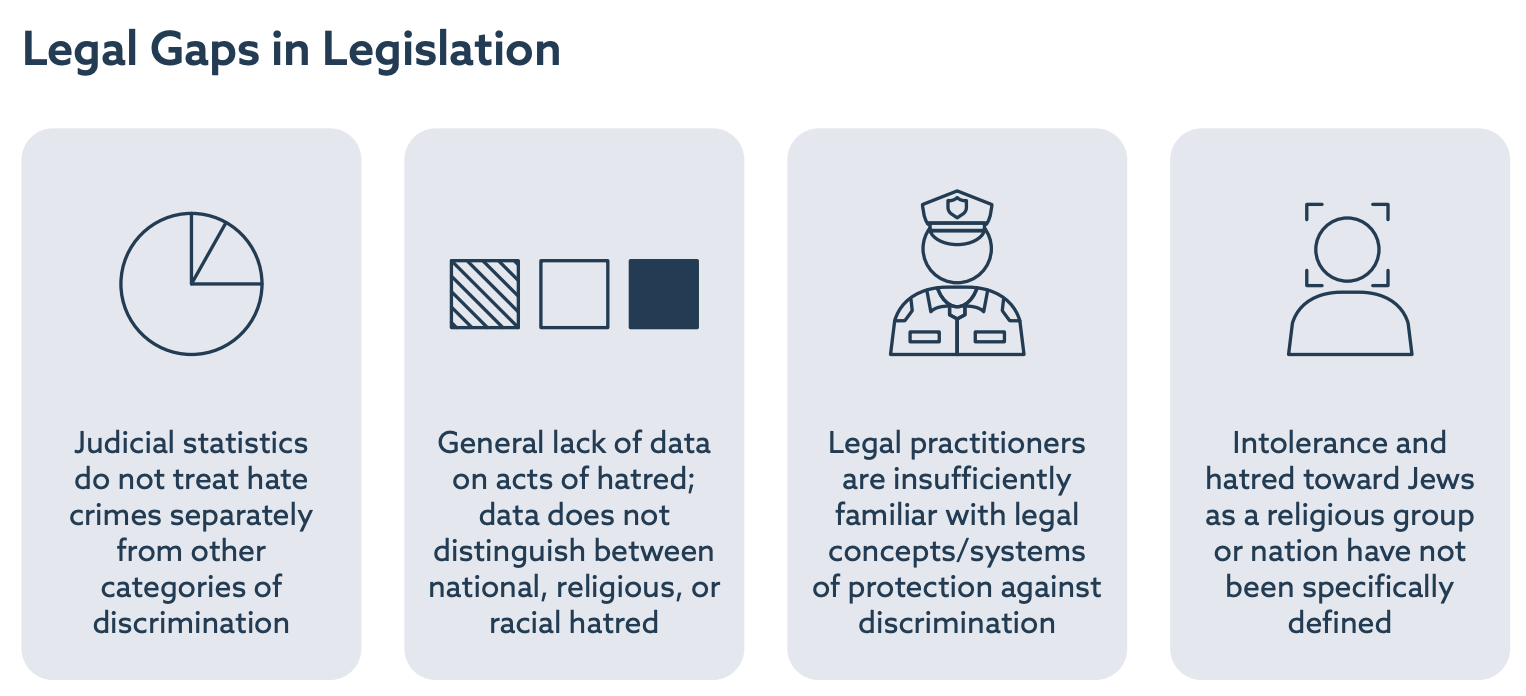

In Albania, public prosecutors are responsible for collecting data on hate crimes. The European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) notes that a comprehensive data-collection system for racist and homophobic/transphobic hate-speech incidents is lacking. According to the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), Albania has not systematically reported hate crime numbers registered by the police.63 Victim and witness protection against hate crimes falls under the usual provisions of protection from discrimination.

Legislation refers to race, among other things, as grounds for protection against unlawful discrimination. As Jews are not recognized as a national minority in Albania, there is no particular reference to antisemitism in legislation. There is also a gap regarding the specific protection of witnesses and victims of hate crimes and antisemitism.64

Institutional Mechanisms

Albania’s legal framework for protecting human rights is broadly in line with European standards, and Albania has ratified most international human-rights conventions. However, enforcement of human-rights protection mechanisms needs to be strengthened, including the roles of the police and the judicial system. International donors have lately begun working with the police and other law enforcement to develop their capacities in identifying hate crimes. High expectations are placed on the large-scale remolding of the judiciary system. This significant reform started in 2016 and aimed to ensure the judiciary’s separation from political influences, to create a more citizen-oriented legal aid system, vetting prosecutors, and setting up new justice institutions.65

In early 2020, as part of Albania’s presidency of the OSCE, a high-level conference, Fight Against Antisemitism in the OSCE Region, was held in Tirana. With official delegations from OSCE participating states, representatives of international organizations, and civil society members, this was the first event of its kind hosted by Albania. The prime minister issued a call to the participating countries to act together with civil society to face the challenges of antisemitism in the OSCE region. Albania has been an observer member of IHRA since 2014 and organizes an annual commemoration of International Holocaust Remembrance Day with its support. The Council of Europe supports the authorities, educational institutions, and civil society in Albania to run awareness-raising campaigns and other educational activities in solidarity with Jewish people and speak up against antisemitic hate speech.

The ECRI maintains that the People’s Advocate (ombudsman) and Commission for the Protection from Discrimination (CPD) have established a very effective and collegial relationship in which both institutions have built on each other’s mandate, capacities, and expertise. Staffing levels at the CPD, as well as in regional offices, have been increased for monitoring and reporting. Over the years, the CPD has compiled examples of best practices dealing with hate speech on ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, and gender identity, under the prohibition of harassment as a form of discrimination. The People’s Advocate and the CPD have made racist and homophobic/transphobic hate speech a prominent topic in their work, acknowledging that this problem must be tackled effectively.66

Media-Monitoring Outcomes

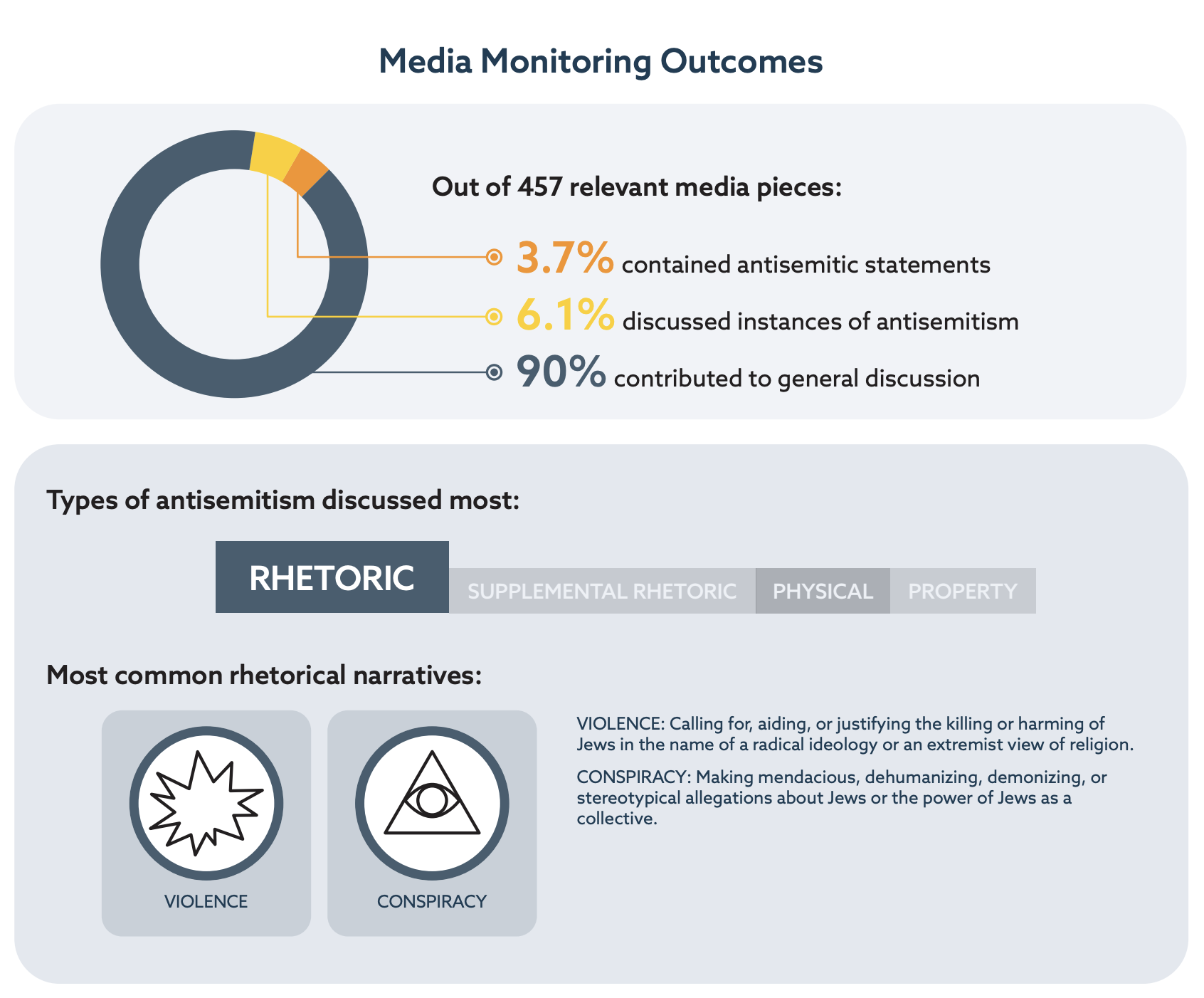

Media monitoring in Albania focused solely on Albanian-language sources. Researchers worked with 457 relevant media pieces.67 Of these, 17 pieces contained antisemitic statements, and 28 discussed concrete instances of antisemitism. The rest of the relevant media pieces contributed to general discussion and news coverage related to the Jewish community worldwide.

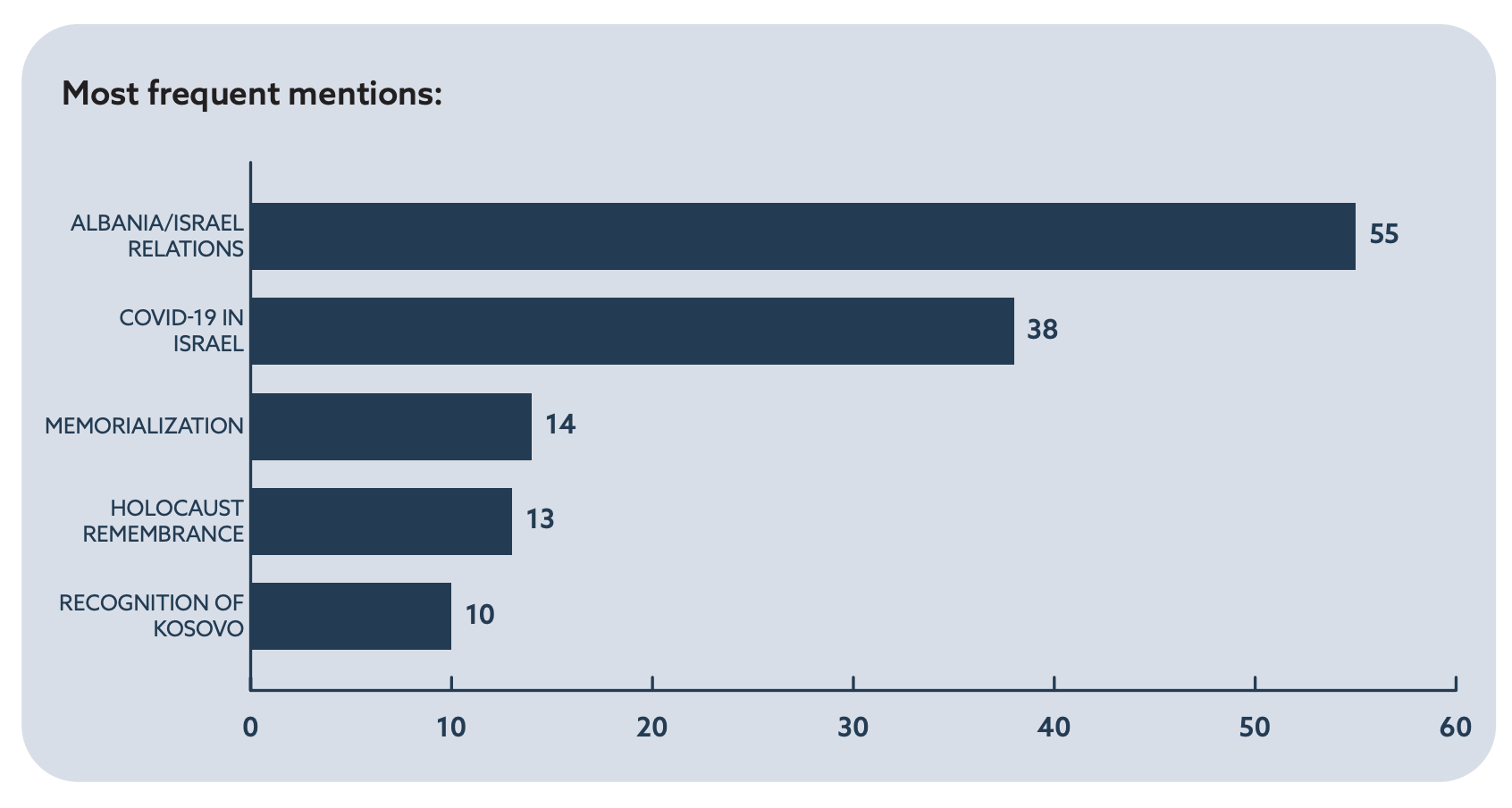

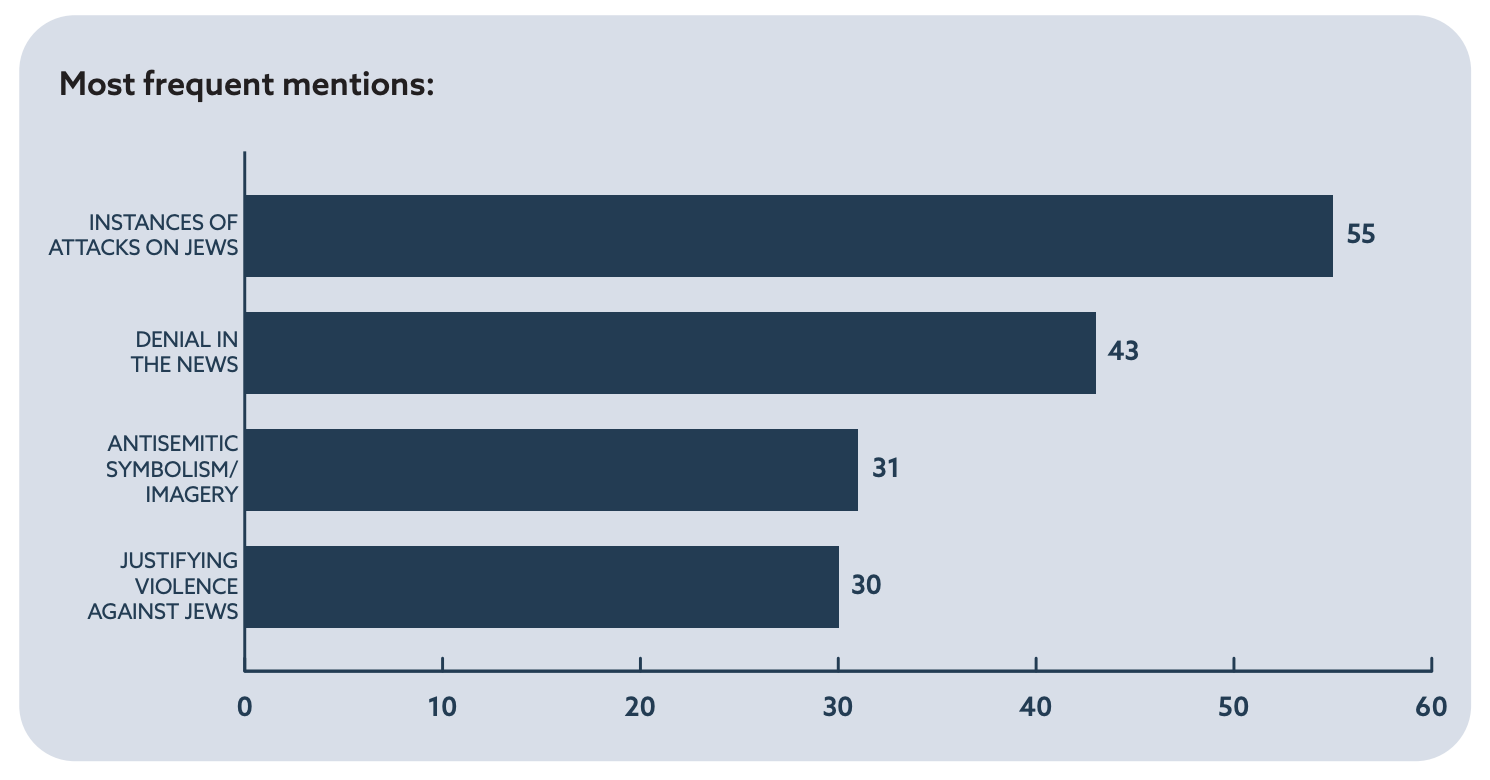

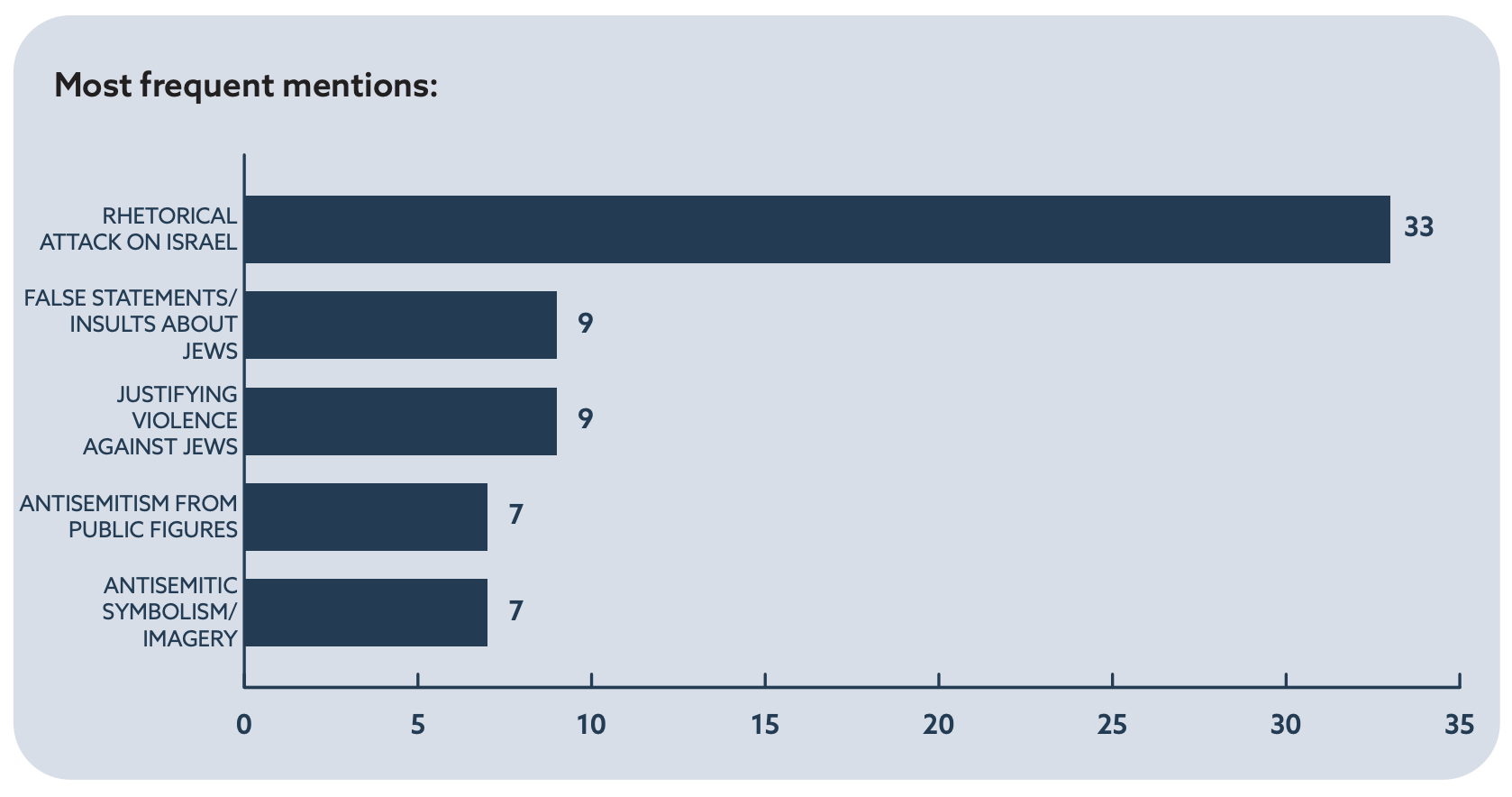

The types of antisemitism that appeared most frequently were rhetoric, conspiracy, and violence.68 Antisemitic statements most commonly took the form of conspiracy (five times) or false (three times). However, the most frequent relevant mentions in the monitored media articles focused on descriptions of the good relations between Albania and Israel (55 tags), COVID-19 in Israel (38 tags), memorialization (14 tags), Holocaust remembrance (13 tags), and the recognition of Kosovo by Israel (10 tags). Antisemitic statements were rarely present, though some traces of antisemitism rhetoric could be observed in relation to conspiracy theories regarding George Soros and Jewish people controlling the world order and economy.

Coverage of antisemitism was focused mainly on Albania. Some online media referred to antisemitism abroad, but this was rare. Most media discussed antisemitism only in relation to Holocaust remembrance.69

Antisemitic Narratives

Antisemitism is not frequently discussed in Albanian media. The only noticeable antisemitic narrative refers to conspiracy theories regarding George Soros’s role in influencing and even controlling Albania’s political process. These theories are primarily created in social and online media, such as private and fringe news portals, and subsequently picked up by other media. Since members of today’s political opposition in Albania use this narrative, it most often appears in news reporting about the political opposition’s activities. However, this narrative is more about Soros’s political impact in Albania as a Jewish philanthropist and donor than about the power of Jews as a collective.

The conspiracy narrative targeting George Soros and his actual or assumed impact on Albanian politics is tied to a larger narrative focusing on foreign actors controlling political decision-making in the country, which is used in political clashes between opposing political actors. The portrayal of Soros as the mastermind of a globalist movement and a left-wing radical who seeks to undermine the established order is now part of Albania’s mainstream political discourse. For instance, the opposition center-right Democratic Party (PD) leader, Lulzim Basha, claimed in 2017 to have been “viciously attacked” by George Soros, his organizations and supporters, because he is an overt Donald Trump supporter.70 He claimed that the international media have attacked him, and he has implicitly argued that Soros controls the mainstream international media. The name Soros crops up frequently in attacks against independent NGOs, journalists, and government critics, and is connected with alleged plans to bring down governments and destabilize countries. Soros’s Open Society Foundation has come under pressure in Albania because it supported judicial reforms currently underway. Some members of parliament (MPs) have called the reforms “Soros-sponsored.”71 In addition, in 2019, President Ilir Meta claimed that Soros was behind a conspiracy to seize control of Albania by interfering in local elections.72 This narrative is also part of a wider anti-Soros campaign in the Western Balkans, as the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) has previously reported.73

George Soros was influential in Albania in the early 1990s because of his extensive support for civil society. This activity elicited some harsh judgments, particularly by the former leader of the Democratic Party of Albania. Sali Berisha, who is also the former President of Albania, continues to claim that “after 4–5 years I realized that this was an almost entirely one-sided investment and George Soros set up a network of associations which in 80-90% of them were the levers of the former communist party, the socialist party that changed its name. It was a marvel of damage to the role and mission of civil society.”74 Though now led by Lulzin e-Basha, the Democratic Party of Albania continues to reinforce the narrative articulated by Berisha, of George Soros controlling judicial reform and financing and supporting only left-wing parties, organizations, and movements to the detriment of the right. Other conspiracy scenarios within this narrative include “Soros is depopulating Albania,” referring to increased migration of Albanian citizens to European countries such as Germany. Other cases relate to Soros’s alleged impact on the higher-education system in Albania, with accusations that former Deputy Minister of Education Taulant Muka is a Soros “handmaid” who blackmails academics to achieve Soros’s goals.75

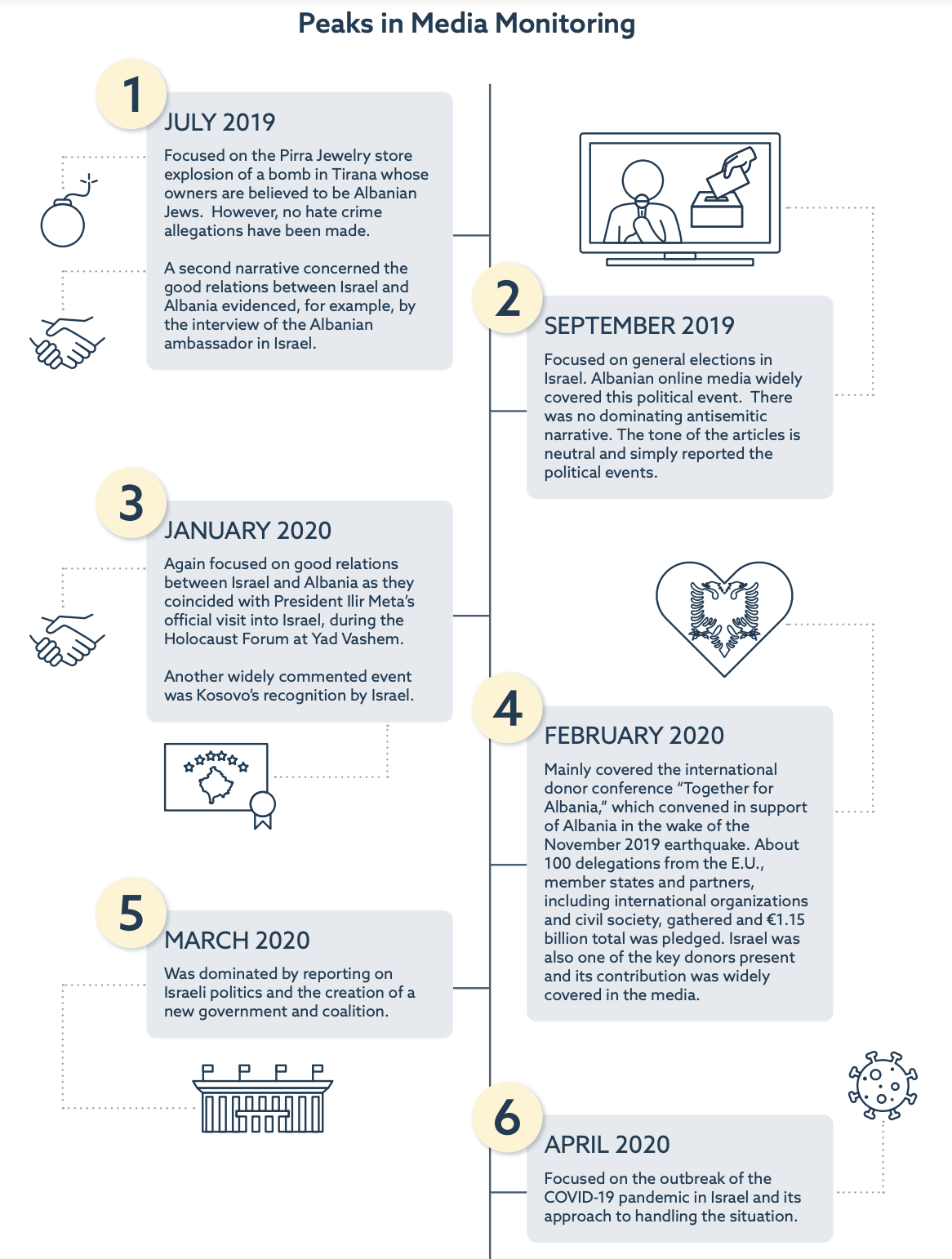

The first time peak — July 2019 — focused on a bomb exploding in a Pirra jewelry store in Tirana whose owners are believed to be Albanian Jews.76 However, no hate crime allegations have been made. A second narrative concerned the good relations between Israel and Albania evidenced, for example, by an interview with the Albanian ambassador in Israel.77

The second time peak — September 2019 — focused on general elections in Israel. Albanian online media widely covered this political event.78 There was no dominating antisemitic narrative. The tone of the articles was neutral and simply reported the events.

The third time peak — January 2020 — again focused on good relations between Israel and Albania as it coincided with President Ilir Meta’s official visit to Israel during the Holocaust Forum at Yad Vashem.79 Another widely covered event was Israel’s recognition of Kosovo.

The fourth time peak — February 2020 — mainly covered an international donor conference convened in support of Albania in the wake of the devastating November 2019 earthquake. The international donors’ conference, Together for Albania, organized by the European Union, took place on February 17, 2020, in Brussels. About 100 delegations from the European Union, member states, and partners, including international organizations and civil society gathered, and €1.15 billion was pledged.80 Israel was also one of the key donors present, and its contribution was widely covered in the media.81

The fifth time peak — March 2020 — was dominated by reporting on Israeli politics and creating a new government and coalition.82

The sixth time peak — April 2020 — focused on the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel and its approach to handling the situation.

Countries Mentioned and Sources

Israel is the country mentioned most often in the monitored media, usually in covering the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel, parliamentary elections, or the Albanian president’s official state visit to Israel. For instance, some headlines included: “New Government to Be Formed in Israel,” “President Meta in State Official Visit in Israel,” and “Surge of COVID-19 Cases in Israel.”

The highest number of relevant mentions discussing antisemitism was found in news sites, primarily online news portals. The media that produced the biggest number of such articles were Shqiptarja.com (an online news portal), BalkanWeb (the online news site of the News24 TV channel, privately owned and one of the oldest established online news portals), Dosja-al (an online news portal developed in the past three years), gazetadita.al (a national newspaper with print and online versions), gazetaimpact.com (an online news portal), gazetatema.net (a national newspaper with print and online versions), izraelisot.al (a news platform focused on Israel and Albania) and oranews.al (private TV).

The media that produced articles containing antisemitic content were the Facebook page of the Anti-Soros Movement Albania, established in 2016, which claims that Soros is organizing a plot to destroy and depopulate Albania.83 The movement is primarily active on social media. Other producers of antisemitic content were lawyer Altin Goxhaj (through his official public-figure account on Facebook), the online news portal gazetatema.net, the JOQ website (a mixture of citizen-created content and an online news portal focused on investigative news, satire, and memes), Gazeta Dita (a daily newspaper) and the online news portals Pamfleti, Syri.net, and Dosja. al, as well as comments under their posts, particularly when the reporting is on right-wing political actors attacking Soros.84

Posts and articles containing conspiracy theories attacking George Soros are directed to all citizens of Albania. It is not possible to identify a strategy through which various audiences are targeted with antisemitic narratives.

Media Monitoring Conclusions